Jombang is a region that intersects many Javanese subcultures, including the Arek, Mataraman, and Pasisiran subcultures. Geographically, Jombang is indeed a region located in the center of East Java, leading to a diverse artistic and cultural landscape in this area. One of the most interesting phenomena is the tension between the Abangan and Putihan groups. This has given rise to a new artistic current in this area, where the art has contexts with the intersection of subcultures and the political conflicts occurring in Jombang.

The class classification has been revealed in the phenomenal book by Clifford Geertz titled “Abangan, Santri, and Priyayi”. Clifford Geertz’s writing may have been refuted in recent research, suggesting that this stratification may only be applicable in the Modjokuto area, not throughout Java (Geertz, 1983). However, it has provided a sufficient depiction of the sociological and anthropological landscape occurring in the Jombang environment because, in the period afterward, the groups in this classification have horizontal conflicts.

In Geertz’s study, it is revealed that these three social trichotomies are an important milestone for examining many things, especially in matters of subculture such as the arts. At the beginning of the 20th century, the priyayi could already be eliminated in this differentiation, as they were preoccupied with their own worldly affairs due to the education program from the ethical politics, coupled with the weakening influence of this group itself. Eventually, in this group classification, only Abangan and Putihan remained.

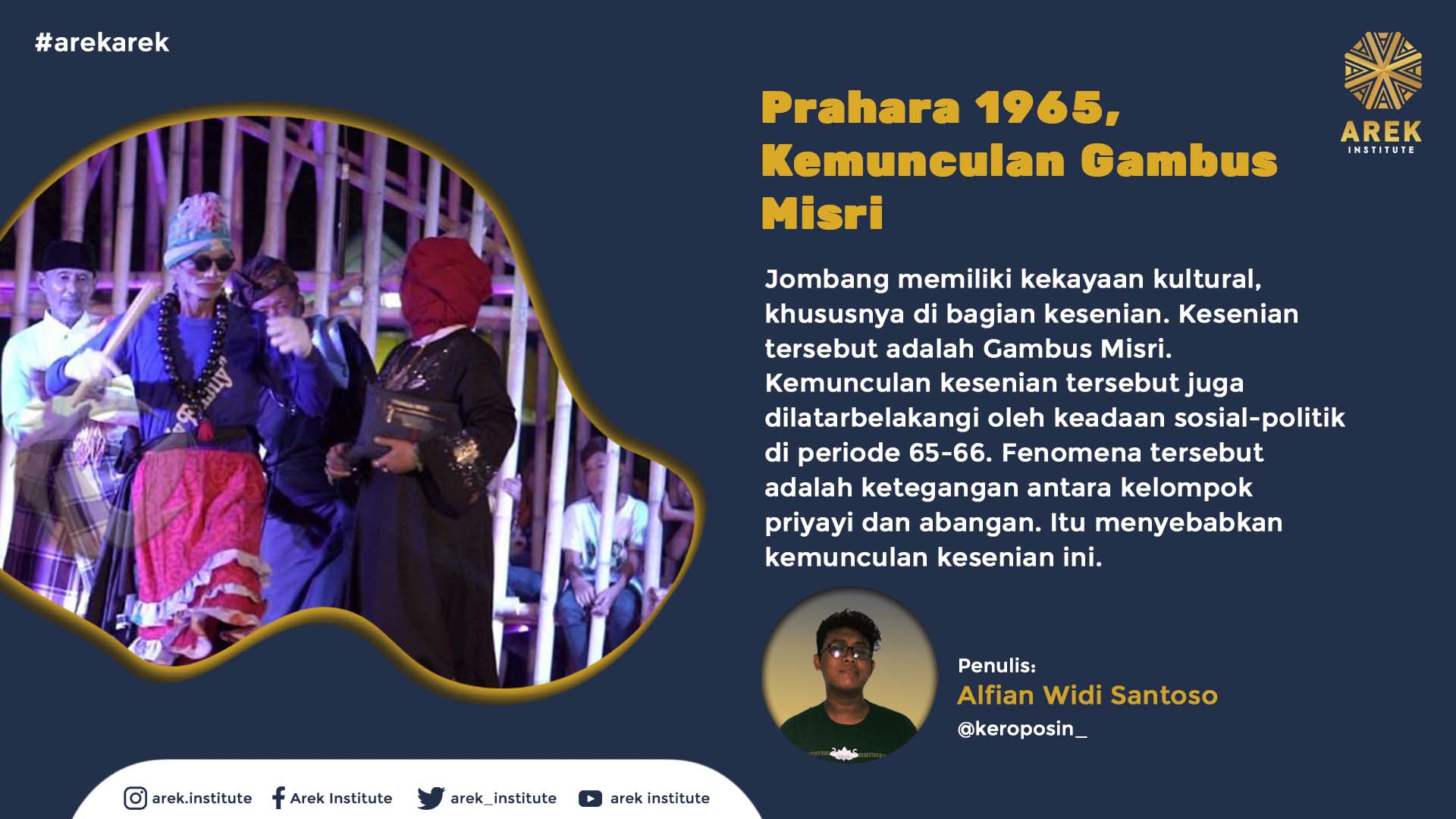

Unfortunately, both the Abangan and Putihan groups often clashed in a cultural context, during colonialism, the Old Order, and the New Order. This significant conflict eventually led to the emergence of many subcultures due to the situation of the times. This phenomenon proved to heat up further in a cultural context. The political transition from the Old Order to the New Order led to many massacres and acts of exclusion against the Abangan group. This phenomenon led to the emergence of a new art stream from the Putihan group, namely Gambus Misri.

Etymologically, Gambus Misri can be divided into two words: Gambus and Misri. Gambus itself means a form of music that spread in the Malay region, and Misri means Egypt, as Egypt is one of the hubs or qiblas of Gambus music itself. One of the factors is the emergence of the singer Umi Kulthum, a very famous artist of her time. Even so, Gambus Misri would later innovate on its own regarding the music it used, especially with the emergence of A. Kadir to Nasida Ria. Additionally, Gambus Misri also follows the Zapin dance pattern, and its comedy is based on Stambul comedy (Sugiarti: 2017).

This article attempts to explore the political and cultural domains that led to the emergence of the Gambus Misri phenomenon in Jombang. This is closely related to the social trichotomy researched by Geertz, as Jombang is not exempt from the cultural phenomena he described. Additionally, numerous Islamic boarding schools (pesantren) are established, and the agrarian community is widespread across the countryside (Dewi, 2019).

The emergence of Gambus Misri represents the santri community’s unease with their entertainment, heavily reliant on religious norms, especially Islam. Especially during the heyday of Ludruk art, which was the only form of entertainment among the lower-middle-class communities, was banned in the pesantren social system around the 1960s. In an interview, Nasrul Ilahi—a Jombang cultural figure—explained the reason for the prohibition of Ludruk art in the Putihan group, stating:

“Ludruk, from the strict santri perspective that follows Molimo teachings, is considered entertainment for people without religion, as Ludruk performances at that time were closely associated with drinking alcohol, sex, gambling, and other sinful activities.”

From this explanation, for the Putihan group, Ludruk art was considered a deviation from religious values. Yet, Ludruk is a performing art that carries a dimension of populism. On the other hand, both the santri and abangan groups shared the same goal: to be free from colonial shackles.

“The kyais could only recommend their students to seek entertainment typical of pesantren, such as the Zapin dance or playing the gambus. Interestingly, people outside the santri community who did not like Ludruk (notably considered negative entertainment at the time) heard about this, and eventually, those outside the pesantren attempted to acculturate Ludruk with pesantren arts. Finally, around one or two decades after Ludruk appeared; Gambus Misri was created from the collective idea of the community,” said Nasrul Ilahi.

In the interview, Nasrul narrated the background of the emergence of this art based on the tension between these two groups because, but Gambus Misri itself also adapted Ludruk art patterns. The significant difference lies in the context of the storyline, comedy, dance, and musical accompaniment, which are more Islamic in nature.

During the Old Order era, there was another polemic between these two social groups. At that time, both arts were always tied to political contests, especially as these contests had segregation and horizontal conflicts, such as differences in groups and teachings represented by the Abangan and Putihan trichotomy.

This political contestation also extended to cultural issues, even worse than during the colonial period. This is evident in the hostility between communist and religious groups. Indeed, many unclear accusations were made between these two groups. In cultural matters, communists had Lekra (People’s Cultural Institution) as an underbow in cultural issues. In this context, Lekra always sponsored Ludruk performances. This is evident in the National Lekra Congress’s decision regarding Film and Drama Art, which stated that in Drama Art, Lekra had the task to investigate, explore, abandon, and develop all kinds of drama that live among the people, supported by one of its work programs to endeavor ideological and artistic education (Yulianti & Dahlan, 2008).

Eventually, through the decision of the National Lekra Congress, it became a marker for future cultural conflicts. Unavoidably, in the ’60s, the tension between the Abangan (Lekra) group and the Putihan group intensified because Ludruk raised very controversial storylines at that time. For example, two famous storylines of its time were “Gusti Allah Ngunduh Mantu” and “Malaikat Kimpoy” (Tempo, 2013). This caused the Putihan group to become greatly alarmed. Even in Kedungsari, Sumobito, Jombang, the community there tried to compete with Ludruk, which was heavily sponsored by Lekra, by establishing Gambus Misri “Bintang Sembilan”—the naming refers to the majority of people in Kedungsari village being members of Nahdlatul Ulama (NU).

This cultural conflict continued until the eruption of the 1965 tragedy, which ended the era of Ludruk due to its storylines that ignited the anger of the Putihan group. However, Ludruk and Gambus Misri have closeness because both arts are tied to the lower class of society, and there were no other entertainments. According to Nasrul Ilahi:

“In Sumobito around the 1960s, Ludruk and Gambus Misri performances alternated, for example, Ludruk in the first week and Gambus Misri in the second week, a phenomenon that continued until Ludruk went dormant due to the events of 1965”

On the other hand, following the turmoil of 1965, it is suspected that many Ludruk performers sought refuge within the Gambus Misri group, as these Ludruk players did not want to be affected by the massacre and exclusion of the Abangan group. This is because Ludruk artists were always associated with the Abangan group, which was notably considered the underbelly of the PKI (Communist Party of Indonesia).

In short, the art of Gambus Misri emerged due to tensions between the Abangan and Putihan groups. Due to this tension, the Putihan group introduced a new stream of art with Islamic dimensions. This art once filled the cultural space of the Jombang community alongside Ludruk art, but during the bloody events of 1965, Gambus Misri became a haven for Ludruk artists who did not want to be eliminated and killed.

0 Comments