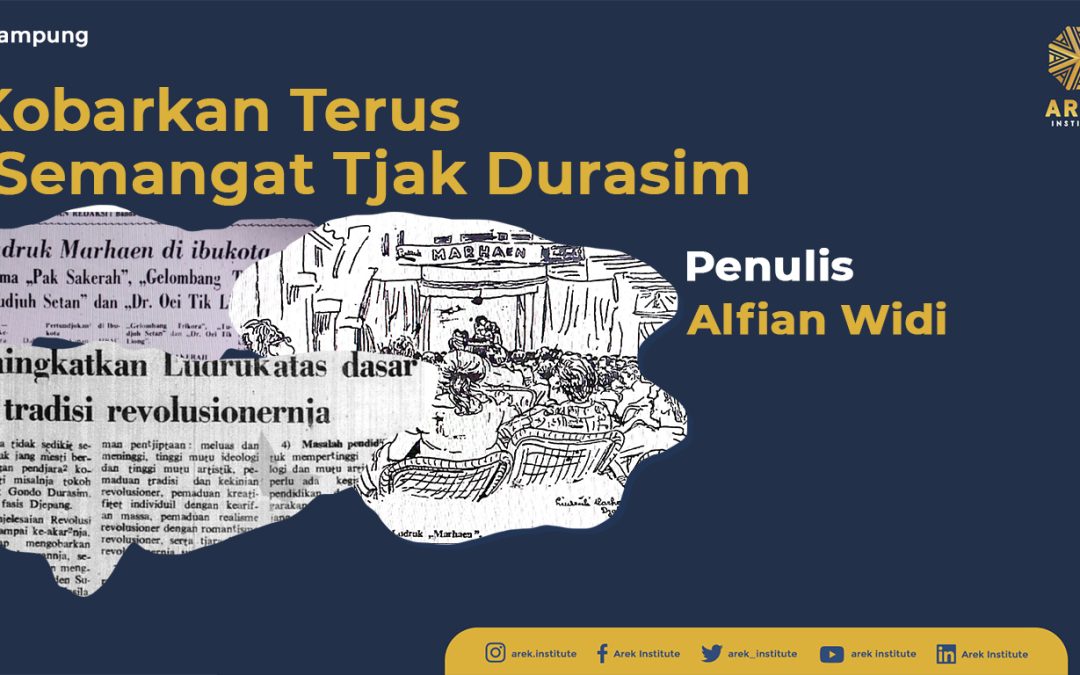

Keep the Spirit of Tjak Durasim Burning: Lekra’s Efforts to Revolutionize Ludruk in the 1960s

Image 1 View of Ludruk “Marhaen”, a sketch by Legowo. Source: Harian Rakjat, 26 September 1965

Alfian Widi Santoso | Alumni History Department in Airlangga University | Associate Research in Arek Institute

In various studies on the history of Ludruk (a traditional Javanese theater form), Lekra (Lembaga Kebudayaan Rakyat, or the Institute of People’s Culture) is often portrayed as an antagonistic figure in its efforts to develop the Ludruk art form. This is illustrated in Tempo’s special edition titled “Lekra and the 1965 Upheaval”, which mentions that Lekra once conducted a cultural offensive through Ludruk performances that featured plays with titles considered offensive to religion, such as “Malaikat Kimpoi” (The Angel Marries), “Gusti Allah Ngunduh Mantu” (God Throws a Wedding), “Matine Gusti Allah” (The Death of God), and others (Tempo, 2013).

Both the book by Saskia Wieringa and Nursyahbani Katjasungkana (2020) and the special Tempo report explain that these plays were merely intended to provoke rural communities to remain critical of their land rights, especially since they were often vulnerable in legal matters. Wieringa and Katjasungkana explain that the play “Matine Gusti Allah” is a simple story about the harsh conditions faced by rural communities, and was meant to commemorate the death of Jesus Christ or Easter (Wieringa and Katjasungkana, 2020).

Ultimately, the phenomenon of controversial Lekra plays is more frequently presented in a negative light, disregarding the factual content of these performances. This issue has also given rise to a partial yet dominant historical narrative about the cultural offensive, with the most logical justification being the limitation of sources. It has also resulted in the loss of fragmented narratives about Lekra, such as the concept of “1-5-1,” one combination of which includes “Good Traditions and Revolutionary Modernity.” Despite the controversy, there were in fact many efforts initiated by Lekra in the context of traditional performing arts that are rarely narrated due to the dominance of anti-communist power structures built after 1965 and entrenched to this day through the cultural hegemony of the New Order regime.

This article aims to fill the gaps in the current narratives surrounding Lekra’s Ludruk. Moreover, it is based on relatively new archival sources that are rarely included in the dominant and problematic narratives about Lekra’s Ludruk. To date, there is only one book that utilizes these sources, namely “Lekra Tak Membakar Buku: Suara Senyap Lembar Kebudayaan Harian Rakjat 1950–1965” (Lekra Didn’t Burn Books: The Silent Voices of the Culture Section of Harian Rakjat, 1950–1965) by Muhidin M. Dahlan and Rhoma Dwi Aria Yuliantri. Even so, that book only presents very limited archival material regarding Lekra’s Ludruk.

Ludruk, Cak Durasim, and Its Revolutionary Actions

One of the most prominent narratives surrounding Cak Durasim is his resistance to Japanese fascism on stage. His iconic parikan (rhymed verses) established him as a pioneering Ludruk performer who embodied both revolutionary and populist values. His emergence cannot be separated from the culture of urban peripheries and the Arek subculture that flourished in East Java, particularly in and around Surabaya.

According to Peacock, Ludruk rarely reached the priyayi (Javanese aristocracy) and santri (Islamic religious community) groups, as various opinions rendered Ludruk controversial. Most of its audience and performers came from the proletarian class, such as street vendors, pedicab drivers, commercial sex workers (CSWs), domestic helpers, and others (Peacock 1987).

The use of coarse or ngoko (informal Javanese) language is a distinctive hallmark of both Ludruk and the Areksubculture itself. This was likely influenced by the rough contours of urban culture, which was filled with migrants seeking better livelihoods. According to Rachman (2022), the rise of the Arek subculture—especially in Surabaya—was an indirect consequence of the alienation that emerged in urban areas during Dutch colonialism (Rachman 2022).

In line with Rachman’s argument, Peacock sees Ludruk as a people’s art or proletarian art. Aside from its close ties with left-wing cultural organizations, Ludruk also emerged as a response to the social inequalities occurring in cities like Surabaya (Peacock 1987). In contrast, urban life since the colonial era was extremely unequal: Europeans lived from one societeit (social club) to another, from one café to the next (Achdian 2023), while the indigenous population lived in poorly sanitized private village ss or even squatted in abandoned buildings due to limited access to urban spaces (Basundoro 2013).

Therefore, it’s unsurprising that Ludruk emerged from humble street performances in markets and evolved into a stage art form featuring stories closely tied to the people’s everyday lives. As part of this response, Cak Durasim, a pioneer of Ludruk, was also a movement activist in the 1930s. His involvement in PBI (Persatuan Bangsa Indonesia, or the Union of the Indonesian Nation), founded by Dr. Soetomo, marked the beginning of his resistance (Rachman 2023).

During the Japanese occupation of Indonesia (1942–1945), Cak Durasim, as a Ludruk artist, resisted in the way he could—by composing satirical and provocative parikan, which later became legendary and ultimately led to his execution by the Japanese. At the same time, he was even reported to have been involved in an underground movement organized by the PKI (Indonesian Communist Party), though the nature of this underground activity remains unclear (Antariksa 2005).

Lekra and the Discourse on People’s Art

“Since its inception, Lekra has consistently unearthed the richness of people’s art across various regions—arts which, until then, could be likened to gold mines that had yet to be explored or exploited. Had Lekra not taken up this task, that gold might have remained forever buried under sand, or even disappeared without a trace.”

—Joebaar Ajoeb, “General Report of the Lekra Central Committee to the First National Congress of Lekra” (1959)

With its guiding principle that “The People are the sole creators of culture,” Joebaar Ajoeb’s statement at Lekra’s First National Congress becomes a certainty: that Lekra would always position the people as the primary source of artistic creation. This aligns with Hersri Setiawan’s statement (2022), which explains that Lekra’s goal was not to produce artists or writers per se, but to cultivate cultural awareness among the people through methods already ingrained in their lives—one of which was through traditional folk art (kesenian rakyat) (H. Setiawan 2021).

Muhidin M. Dahlan and Rhoma Dwi Aria Yuliantri (2008) further explain that cultural workers under Lekra carried out a collective mission rooted in their own awareness: to develop people’s art forms that otherwise only existed from village to village in a stagnant state, and would inevitably become marginalized and eventually disappear (Dahlan and Yuliantri 2008).

The use of people’s art became a highly feasible option because society was already more familiar with it than with modern forms such as opera, drama, choir, and others. Lekra, as a cultural actor, recognized that traditional art—originally perceived merely as entertainment—could be transformed into a medium for public consciousness. This was in line with the 1-5-1 principle: “Good traditions and revolutionary modernity.” Thus, Lekra’s cultural workers felt it necessary to establish creative institutions aimed at facilitating and organizing artistic communities already embedded in society, in order to “expand and elevate” people’s art (Dahlan and Yuliantri 2008).

In the context of traditional performing arts, for instance, there is Ludruk from East Java, which had long held characteristics of populism and organic resistance in its performances—such as the stories of Pak Sakera, Sarip Tambak Oso, and others. In fact, the very creation of Ludruk stemmed from lower-class resistance, exemplified by its pioneer, Cak Gondo Durasim, whose famous parikan voiced opposition to Japanese fascism:

“Pagupon omahe doro, melu Nippon tambah sengsoro”

(“A dovecote is the home of doves; joining the Japanese only brings more misery.”)

In the 1960s, Ludruk underwent a significant renewal, led by the leftist cultural movement such as Lekra. According to HR Minggu (People’s Daily Sunday edition), on January 31, 1965, the East Java branch of Lekra established the “Cak Durasim” Ludruk School, attended by 60 Ludruk artists from across East Java.

Another example is found in the field correspondence column of HR Minggu, which replaced the “Culture Section” (Ruang Kebudajaan) in Harian Rakjat starting in 1963. In the March 14, 1965 edition of HR Minggu, an article describes an experimental idea by M.D. Hadi, involving the creation of new wayang (shadow puppet) characters that reflect the people and are free from palace-centric hegemony. This experiment included plays rooted in the lives of common people. This aligns with Hersri Setiawan’s account during his time as head of Lekra’s Central Java branch, where the organization promoted the concept of “Fable Wayang” targeted at children, and wayang narratives grounded in the populist tradition (H. Setiawan 2021).

Lekra and Ludruk: What Has Been Done?

“Will Ludruk always be branded as cheap art and never accepted by intellectual circles?!” Thus spoke Bambangsio in his correspondence titled “The Second Lestra Surabaya Symposium: On Ludruk Drama Experiments”, published in HR Minggu, May 24, 1964. This statement aligns with the words of Gregorius Soeharsojo in his memoir, explaining his fondness for Ludruk: “I enjoy Surabaya’s Ludruk the most, with its witty rhymes that playfully jab at various issues. The wholesome humor of its comedians always sides with the common people” (Goenito, 2016).

Both Soeharsojo’s appreciation and Bambangsio’s inquiry reflect how, in the 1960s, Ludruk was no longer merely a folk performance watched only by the lower class—it was embraced across societal layers. Bambangsio noted that Ludruk was undergoing significant development at the time, attracting broader audiences. The invitation for Ludruk Marhaen to perform at the State Palace in both 1958 and 1964 was crucial evidence of this growth, marking a turning point for adapting Ludruk to its contemporary context (Harian Rakjat, 1958).

Several key moments illustrate how the leftist movement, particularly Lekra, worked to develop Ludruk as a noble tradition fused with revolutionary modernity in line with the 1-5-1 principle. The first moment, as documented in Harian Rakjat, was the participation of Ludruk Marhaen actors in the film Kunanti di Djokdja (1959). The second was the East Java Ludruk Institution Conference held from July 30 to August 1, 1964, which resolved, among other things, to support the Ministry of Education and Culture’s directive to oppose imperialist cultural penetration. The third was a series of events in 1965: Ludruk Marhaen was invited again to perform at the State Palace, the Tjak Durasim Ludruk School was founded, and the First National Ludruk Congress was held, eventually establishing the United Ludruk of Indonesia (PERLINDO).

Ludruk gained national attention through the film Kunanti di Djokdja (1959), which featured Ludruk actors. An advertisement in Harian Rakjat on June 19, 1959, claimed the film offered fresh humor while portraying the 1945 Revolution through laughter and tears. It was also touted as a major film of the year with the potential to “explode” the capital’s audience.

This marked an important experiment—integrating folk art like Ludruk with modern tools such as film. The film’s success, directed by Tan Sing Hwat, received positive responses from various audiences across Indonesia. Through cinema, many Indonesians were introduced to Ludruk, which had previously been popular mainly in East and Central Java. Additionally, the film sought to counteract the growing influences of Americanism and Indianism in Indonesia’s film industry (Harian Rakjat, 1959). The success of this experiment earned Tan Sing Hwat a Best Screenwriter award at the 1960 Indonesian Film Festival (A. Setiawan, 2019).

The film’s success inspired Ludruk artists affiliated with Lekra to participate in the modernization of folk art in line with the principle of “noble tradition and revolutionary modernity.” This was reflected in the resolutions of the first East Java Ludruk Institution Conference (July 30 – August 1, 1964), which declared that Ludruk organizations would actively oppose American imperialist films and volunteer to fill content gaps in the film industry. The 250 participating Ludruk organizations also emphasized that Ludruk should not only be humorous but also raise political awareness, combat superstition, and promote unity. At this conference, a new leadership was chosen for the East Java Ludruk Institution: J. Shamsudin (Ludruk Marhaen) as Chair, M. Nasrip as Vice Chair, and Asmirie as Secretary (Harian Rakjat, 1964).

On January 31, 1965, HR Minggu reported concrete steps taken after the East Java Ludruk Conference. One such step was the founding of the Tjak Durasim Ludruk School, aimed at advancing Ludruk as a revolutionary folk art. The school was officially opened by Shamsudin, the chair of the Ludruk Institution, and welcomed 60 Ludruk artists from various parts of East Java as its first cohort. This initiative also served to prepare for the upcoming First National Ludruk Congress scheduled for April (Harian Rakjat, 1965a).

Unfortunately, the Congress did not take place in April, likely because Ludruk Marhaen had another performance scheduled at the State Palace (Harian Rakjat, 1965). Eventually, the First National Ludruk Congress and Festival were held from July 11 to 16, 1965, at Balai Pemuda, Surabaya. Under the slogan “Strengthen the Integration of Ludruk with the People and the Revolution”, the congress was reportedly attended by 25,000 Ludruk artists, according to Harian Rakjat (Harian Rakjat, 1965a).

Topics discussed included: “The History and Development of Ludruk,” “Artistic Issues in Relation to Audience,” and “Modernization and Organization of Ludruk.” The congress produced important resolutions aimed at advancing Ludruk as revolutionary folk art aligned with Sukarno’s political agenda, including:

- Ludruk must foster a national culture serving workers, farmers, fishermen, and soldiers.

- Form a centralized Ludruk organization called United Ludruk of Indonesia (PELINDO).

- Implement necessary reforms to enhance its commitment to the people and revolution, while continuing its revolutionary tradition.

- Focus on education to improve Ludruk’s ideological and artistic quality.

- Declare Tjak Gondo Durasim a national Ludruk hero.

- Ensure Ludruk artists integrate with the people and the revolution.

- Host Ludruk festivals to encourage growth.

- Promote cultural cooperation with state apparatus in line with revolutionary character (Harian Rakjat, 1965c).

The Congress also discussed writing a history of Ludruk and artistic experimentation. These efforts demonstrated Lekra’s approach to developing regional culture. As M.H. Lukman, Vice Chair I of the PKI Central Committee, stated:

“The idea that revolutionizing regional drama would harm its popularity is not only inaccurate but has already been refuted by revolutionary drama artists. Precisely through renewal and technical enhancement rooted in tradition, revolutionary artists have shown that regional drama can achieve higher ideological and artistic quality while gaining broader appeal” (Harian Rakjat, 1965b).

Following the congress, a Ludruk Performance Week Festival was held, in which Ludruk organizations from various regions performed and were judged. The festival winners were: Ludruk “Arumdalu” from Jombang (1st), Ludruk CGMI Surabaya (2nd), and Ludruk Sidoarjo (3rd). Honorable mentions included teams from Kudus, Jember, Blitar, “Mawar Merah” from Rembang, and Lamongan (Harian Rakjat, 1965d).

After the congress and festival, PERLINDO, the umbrella organization for Ludruk, began working. The only announcement published in Harian Rakjat (September 12, 1965) urged all member organizations to study Sukarno’s Takari speech. PERLINDO reminded its members:

“Our attitude toward both traditional and foreign cultures must be the attitude of the national democratic revolution: we strip feudalism from the old culture and eradicate imperialism from foreign cultures” (Harian Rakjat, 1965e).

Tragically, the 1965–1966 catastrophe struck. Cultural activities were paralyzed, including Ludruk. All performances were banned for two to three years, according to Cak Kartolo (Harian Rakjat, 1965). In the aftermath, Ludruk organizations were often brought under military institutions. Under the New Order regime, Ludruk became a propaganda tool and lost the revolutionary spirit of Tjak Gondo Durasim, who had once fought fiercely against oppression.

References

Achdian, Andi. 2023. Ras, Kelas, Bangsa: Politik Pergerakan Antikolonial di Surabaya Abad Ke-20. Tangerang: Marjin Kiri.

Antariksa. 2005. Tuan Tanah Kawin Muda: Hubungan Seni Rupa dan Lekra 1950-1965. Yogyakarta: Yayasan Seni Cemeti.

Basundoro, Purnawan. 2013. Merebut Ruang Kota: Aksi Rakyat Miskin Kota Surabaya 1900-1960an. Tangerang: Marjin Kiri.

Dahlan, M. Muhidin, dan Rhoma Dwi Aria Yuliantri. 2008. Lekra Tak Membakar Buku: Suara Senyap Lembaran Kebudayaan Harian Rakjat 1950-1965. Yogyakarta: Merakesumba.

Dokumen (I): Kongres Nasional Pertama Lembaga Kebudajaan Rakjat. 1959. Bagian Penerbitan Lembaga Kebudajaan Rakjat.

Goenito, Gregorius Soeharsojo. 2016. Tiada Jalan Bertabur Bunga: Memoar Pulau Buru dalam Sketsa. Yogyakarta: Insist Press.

Harian Rakjat. 1958. “Marhaen DI ISTANA,” 12 April 1958.

Harian Rakjat. ———. 1959a. “Adv. Kunanti di Djokdja,” 19 Juni 1959.

Harian Rakjat. ———. 1959b. “Film Ludruk KUNANTI DI DJOKDJA: Peranan wanita dilakukan oleh para pria,” 20 Juni 1959.

Harian Rakjat. ———. 1965a. “Sekolah Ludruk ‘Tjak Durasim’ Surabaja,” 31 Januari 1965.

Harian Rakjat. ———. 1965b. “Kongres Nasional Ludruk,” 7 Maret 1965.

Harian Rakjat. ———. 1965c. “Wkl. WALIKOTA SURABAJA PADA KONGRES LUDRUK : Kobarkan terus semangat Tjak Durasim,” 18 Juli 1965.

Harian Rakjat. ———. 1965d. “KONGRES NASIONAL KE-I LUDRUK SUKSES: NASAKOMKAN RRI-TV SELURUH INDONESIA,” 25 Juli 1965.

Harian Rakjat. ———. 1965e. “DPP PERLINDO: DENGAN TAKARI DJADIKAN LUDRUK DUTA MASA DAN DUTA MASSA,” 12 September 1965.

Harian Rakjat . 1965. “Ludruk Marhaen di ibukota,” 28 Maret 1965.

Harian Rakjat. 1964. “KONF. LEMBAGA LUDRUK DJATIM: Bubarkan Ampai, Ritul DFI,” 9 Agustus 1964.

Harian Rakjat. ———. 1965a. “Kongres Nasional LUDRUK dibuka hari ini,” 11 Juli 1965.

Harian Rakjat. ———. 1965b. “M.H. LUKMAN: Dengan semangat Tjak Durasim kobarkan ofensif revolusioner dibidang ludruk,” 13 Juli 1965.

Harian Rakjat. ———. 1965c. “Meningkatkan Ludruk atas dasar tradisi revolusionernja,” 22 Agustus 1965.

Peacock, James L. 1987. Rites of Modernization: Symbolic and Social Aspects of Indonesian Proletarian Drama. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Rachman, Anugrah Yulianto. 2022. “Kemunculan Kota, Kemunculan Arek Surabaya.” Arek Institute. 8 Januari 2022. https://www.arekinstitute.id/blog/2022/01/08/kemunculan-kota-kemunculan-arek-surabaya/.

———. 2023. “Durasim (1).” Arek Institute. 26 Desember 2023. https://www.arekinstitute.id/blog/2023/12/26/durasim-1/.

Setiawan, Andri. 2019. “Riwayat Tan Sing Hwat.” Historia. 11 September 2019.

Setiawan, Hersri. 2021. Dari Dunia yang Dikepung Jangan dan Harus: Kumpulan Surat, Esai, dan Makalah. Yogyakarta: Sekolah mBROSOT & Kunci Forum dan Kolektif Belajar.

Tempo. 2013. Lekra dan Geger 1965. Tempo. Jakarta: Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia.

Wieringa, Saskia E., dan Nursyahbani Katjasungkana. 2020. Propaganda & Genosida di Indonesia: Sejarah Rekayasa Hantu 1965. Disunting oleh Rahmat Edi Sutanto. 1 ed. Depok: Komunitas Bambu.