The Actual Problem: Cleanliness and Health Problems in Pegirian River in Colonial Period

Alfian Widi Santoso | Student of History Departement in Airlangga Unviersity | Arek Institute Associate Researcher

Surabaya has long faced health issues related to water. This is evidenced by a petition to the Queen of the Netherlands, published in the Soerabajasch Handelsblad at the end of the 19th century, which concerned the provision of clean water for the population. The petition, created for the benefit of the European community, was motivated by the escalating cholera problem in Surabaya, as well as fears regarding the potable water conditions in Surabaya following John Snow’s discovery of the link between poor drinking water hygiene and the spread of cholera (Achdian, 2023).

The petition was eventually granted several years later, coinciding with Surabaya’s designation as a municipality. Nevertheless, issues regarding community hygiene and water remained problematic until the end of Dutch rule in Indonesia in 1942. This was due to disparities, where Europeans easily accessed water directly supplied to their homes, in contrast to the indigenous population who had to queue for water as each village was only equipped with one pump (Huda, 2016).

One of the impacts of this unequal policy can be observed in the Pegirian River, where hygiene issues were seriously highlighted, both in terms of problems and solutions, by two renowned authors of Dutch descent: H.F Tillema in his extensive volumes of Kromoblanda and Von Faber in his monumental second work, Nieuw Soerabaia. This writing highlights the Pegirian River case in the Nyamplungan district, which was a focus of the Surabaya government, and will discuss the government’s policies at the time in addressing this issue.

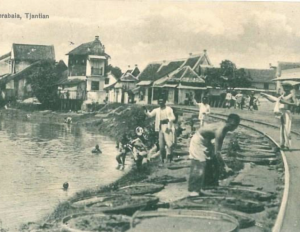

Image 1. The banks of the Pegirian River in the Nyamplungan District. Source: Von Faber, 1933, Nieuw Soerabaia

The Nyamplungan case is one among many health issues in Surabaya, but it received special attention from the Surabaya municipal government, as evidenced by the serious focus of Von Faber in Nieuw Soerabaia. In the book, the chapter on Health Care, specifically on Typhoid Fever, features a comparative photo of the banks of the Pegirian River in the Nyamplungan district, showing a change in the river steps from terraced to gentle.

According to Von Faber, the banks of the Pegirian River were filled with piles of human feces, disposed of indiscriminately. Von Faber noted that this reckless disposal of feces posed a significant problem related to the spread of Typhoid Fever, caused by the Salmonella Typhi virus transmitted through the consumption of food and drink contaminated by the feces of infected individuals. It can be concluded that this situation arose because some people still consumed food or drink sourced from the Pegirian River, such as drinking water or river-derived products, among others.

Image 2. The banks of the Pegirian River in the Nyamplungan district after renovation. Source: Von Faber, 1933, Nieuw Soerabaia

This issue was not confined to the banks of the Pegirian River passing through the Nyamplungan district but was prevalent along the entire length of the Pegirian River. This concern was voiced by Katjoeng Moeda in the “Proletar” newspaper, affiliated with the Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI) in Surabaya, on September 25, 1925. In his complaint about the Surabaya government’s sluggishness in addressing community cleanliness, Katjoeng Moeda wrote:

“At the Girikan River, starting from Gili Ketapang, when the water is stagnant, numerous men and women sit closely together. Not to catch a breeze… but to defecate, producing what could be called ‘sausage bread’.”

The ‘sausage bread’ Katjoeng Moeda referred to was feces. The quoted sentence illustrates a common behavior of defecating in the river, which can be said to mark the beginning of disease spread among the indigenous population. According to Von Faber and the Surabaya government of the time, this issue was deeply ingrained in the community—even after numerous educational efforts, which was evidenced by the accumulation and continuous renewal of feces. Indeed, the feces problem necessitated direct government intervention to resolve it. This was reflected in a report by the De Indische Courant newspaper on December 2, 1927, mentioning that the health department conducted an on-site review of waste disposal in Wonokusumo and would also visit Nyamplungan to discuss issues related to community health and hygiene.

A month later, the same newspaper provided an overview of the conditions in Nyamplungan and the steps to be taken to address this issue. In De Indische Courant, published on January 9, 1928, under the headline “Onhygiënisch Soerabaia” (Unhygienic Surabaya), an opening sentence poignantly described the Nyamplungan area, “Nyamplungan, the filthy…”. The news excerpt roughly went as follows:

“In these clumps of feces, residents of the densely populated villages of Njamploengan and Kertopaten defecate along the riverbanks without any shelter. The feces, left along the riverbanks, are carried back and forth by the tide, causing a continuously disgusting stench to pollute the environment. It would be a blessing for the community if the city government were to build 13 public baths and private facilities along the Pegirian. One of which is already under construction,” said the author.

The improvement of the riverbanks (in Javanese: plengsengan/trap) at least reduced the community’s habit of defecating in the river, a habit that, according to Von Faber, was very difficult to eliminate. These improvement efforts had been planned since 1928 by the B.O.W (Burgerlijke Openbare Werken/Public Works Department) along with the Surabaya health department for immediate implementation, in the interest of public health.

The renovations were not limited to the riverbanks but also included other improvements, such as providing 13 public toilets (ponten) at various points along the Pegirian River. Additionally, a number of hygiene facilities were planned to be built in the villages to train the community to live clean and hygienically. Despite these efforts, the issue persisted and continued, with weekly reports in the De Indische Courant newspaper on community health and diseases arising, especially those related to hygiene. Interestingly, the Nyamplungan area still faced the same diseases (typhoid fever, typhus A., and diphtheria) into the 1930s, even though various hygiene facilities had been constructed.

The Actual Problem!

Indeed, this issue could not be resolved spontaneously, as initially planned by the Surabaya Municipal Government in the early 1930s. The health problem and the planning undertaken by the Surabaya government garnered harsh criticism from the “Proletar” newspaper in its column titled “Tjiamah Tjioeng”. In the January 25, 1925 edition of Proletar, Si Sawoet wrote in this column under the poignant title, “The Government Wants Health, But Lets Disease Close By”, blending criticism and satire towards the Surabaya government. Si Sawoet wrote:

“…Try walking once via Gembong gas factory and Njamploengan street to Pegirikan, your nose would be assaulted, if not covered, by the stench of human… leftovers. It’s not wrong if someone who has grown hardened, then squats showing their behind to the public to… dispose, because to defecate in privacy, one must actually pay… to the government. Municipal Cleaning Service, look there’s a stink service.”

According to Si Sawoet’s account, the Surabaya Municipal Government was neglectful of the health conditions of the lower-class community in Surabaya. Moreover, Si Sawoet suggested that the government appeared to act on making Surabaya cleaner, but the Surabayan citizens, especially the indigenous population, never received adequate and free access. According to Si Sawoet, they (the government) never looked at the actual conditions and only speculated theories in parliament, even stating:

“Theory on paper is always clean, but the practical evidence is… embarrassingly far from it…”

This is in line with the detailed explanation by Jean Gelman Taylor in her essay “Bathing and Hygiene: Histories from the KITLV Images Archive” included in the anthology “Cleanliness and Culture: Indonesian Histories”. In the article, Taylor elucidates the complex issues surrounding why the indigenous population engaged in domestic work and private matters in public spaces like rivers, closely related to the economic issues of the community, especially the indigenous people.

Taylor logically explains that this occurs due to the socio-economic conflict underpinning it all, where the indigenous community, as the third-class society, lacks adequate access to hygiene because:

“First, their homes, often made of woven bamboo, likely do not have a bathroom; if there is one, they must carry water from the river for daily needs such as bathing, washing, and latrines (MCK); Second, the indigenous community is provided with only one water pump per village. This is starkly contrasted with the European community who can easily access clean water. Even through the waterleiding policy, the government could supply water to every European house through the available pipes.”

These two reasons ultimately left the indigenous community with the only option of performing domestic work and private matters in the river, as had been done by previous generations, although the motives were significantly different.

Image 3. Community activities around the river (Cantian), including children bathing, women washing, and the use of riverbanks for drying food. Source: Van Ingen

In the context of Surabaya, Taylor’s argument is validated, showing that the indigenous population struggles with the clean water crisis in their villages, with the government, expected to serve the community, being perceived as absent or negligent. Katjoeng Moeda articulated this critique towards the Gemeente Surabaya at the time, accusing the government of being extortionate and motivated by profit.

“When they do provide services, the government does not forget to ask for a cent from each person bathing and another cent from those using the latrine. Now, because of the government’s money-minded politics, the public suffers. That is, if you walk there (around the Pegirian River), you must hold your breath to avoid suffocating.”

Again, such cases cannot be spontaneously resolved as mentioned by Von Faber or the Surabaya government at that time, but must be accompanied by adequate infrastructure and economic development for the indigenous community. This aligns with Dr. Soetomo’s criticism, who argued that the government must urgently attend to the plight of the indigenous people, especially those living under bridges and along riverbanks.

According to Purnawan Basundoro in his book “Merebut Ruang Kota: Aksi Rakyat Miskin Kota Surabaya 1900-1960an” (Seizing Urban Spaces: Actions of the Urban Poor in Surabaya 1900-1960s), the lower class of Surabaya (especially migrants) who lacked the capital to build a house, ended up using riverbanks and under bridges as places of residence or to construct their homes.

Furthermore, this issue persists to the present day, as detailed by Roanne van Voorst in her book “The Best Place in the World: An Anthropologist’s Experience Living in a Jakarta Slum.” Voorst notes that constructing homes on riverbanks is a common practice among Jakarta’s migrants lacking sufficient capital, as vacant land like riverbanks become a solution, given the weak government regulations on this matter.

These studies demonstrate that the issue of riverbank living has been a continuous problem from the colonial period to the present day. Historians and anthropologists discussing riverbank life will never run out of issues to address. Hence, this lifestyle becomes a matter of concern for both city governments and academics.

In summary, the pattern of village life, where private and domestic spaces are inseparable, has been established since the colonial period. In the current era, this pattern has only shifted in activities and behaviors. However, the limitation in separating private and public spaces still remains unresolved.

References

- De Indische Courant. Gezondheid-Inspectie. 2 Desember 1927

- De Indische Courant. Onhygiënisch Soerabaia. 9 Januari 1928

- De Indische Courant. Besmettelijke Ziekten. 13 Februari 1931

- Si Sawoet. Tjiamah Tjioeng!! Goeminta Maoenja Sehat, tetapi Penjakit biar Dekat. Proletar. 10 Mei 1925

- Katjoeng Moeda. Tjiaaamah Tjiiiioeng!!!, Goeminta Soerabaja. Proletar. 20 September 1925

- Andi Achdian. 2023. Ras, Kelas, Bangsa: Politik Pergerakan Antikolonial di Surabaya Abad ke-20. Tangerang: Marjin Kiri

- G.H. von Faber. 1933. Nieuw Soerabaia: De Geschiedenis van de Indië’s Voornaamste Koopstad in de Eerste Kwarteeuw, Sedert Hare Instelling 1906-1931. Soerabaja: N.V Boekhandel en Drukkerij H. Van Ingen

- H.F. Tillema. 1916. Kromoblanda: Over ‘t vraagstuk van ,,Het Wonen” in Kromo’s groote land. Den Haag: N.V. Electrisch Drukkerij en Uitgave Maatschappij ,,de Atlas”

- Nur Huda. 2016. PERAN GOUVERNEMENT WATERLEIDING TERHADAP PENYEDIAAN AIR BERSIH DI SURABAYA TAHUN 1900-1923. Skripsi. Surabaya: Universitas Airlangga

- Purnawan Basundoro. 2013. Merebut Ruang Kota: Aksi Rakyat Miskin Kota Surabaya 1900-1960an. Tangerang: Marjin Kiri

- Roanne van Voorst. 2022. Tempat Terbaik di Dunia: Pengalaman Seorang Antropolog Tinggal di Kawasan Kumuh di Jakarta. Tangerang: Marjin Kiri