by Penelitian Arek | Sep 4, 2025 | Kelana Masa

Doni Rahma | Anthropology FISIP Unair Student | Arek Institute Researcher Network

Almost 100 years ago, on March 11, 1917, in Surabaya, a movement called Djawa Dipa was born, opposing the feudalistic practices of the time. According to various records, the movement was first initiated in two locations: the Oost Java Bioscoop building (now a shopping complex in the Aloon-aloon Contong area) and the Oost JavaRestaurant. From its inception, Djawa Dipa aimed to equalize the use of the Javanese language by abolishing its hierarchical structure. In other words, unggah-ungguhing basa (the stratified levels of Javanese language such as ngokoand krama) had to be eliminated. The Krama class, referring to the lower layers of Javanese society, became the movement’s main focus because equality for them was of utmost importance. Until then, the hierarchy in the use of the Javanese language had only widened the gap of social stratification and reinforced unfair treatment against them (Thamrin, 2022).

One of the key figures behind the birth of Djawa Dipa was Tjokrosoedarmo, the leader of the SI (Sarekat Islam) Surabaya branch — a native arek Suroboyo from the Plampitan neighborhood, who came from a priyayi (noble) family background. However, in contrast to his aristocratic origins, he became a vocal critic of the rules governing the use of krama (high-level Javanese language). For him, a language structure built on rigid hierarchy was not a tool for communication, but rather a wall of oppression — something that burdened the Javanese people. This was evident in a fragment of his radical ideas, delivered during a speech at the formation of the Djawa Dipa committee, which was also published in the Sinar Djawa newspaper, March 15, 1917 edition.

”…telah njata kita ketahoei, sampai saat ini, dan sampai zaman perobahan ini, atoeran bahasa Djawa ”kromo” itoe hanjalah membikin soesah kita Djawa sadja. Berlantaran atoeran bahasa Djawa ”Kromo” itoe tidak sedikit bilangannya…Maka ketjelakaan dan kesengsaraan pendjara itoe bagi kita boekan bangsa ”sastrawan” hanjalah lantaran soesahnja atoeran bahasa Djawa ”kromo” ada di moeka persidangan hakim”

(…it is clear to us, even up to this moment, and into this era of change, that the rules of the Javanese ‘krama’ language only bring hardship to us Javanese. Because of these ‘krama’ language rules—of which there are no small number… Misfortune and the suffering of imprisonment for us, who are not a ‘literary’ people, are merely caused by the difficulty of these ‘krama’ rules when faced in front of the judge’s court.)

In its time, Djawa Dipa appeared to be supported by prominent figures, including Tjokroaminoto of Sarekat Islam itself. Although Tjokroaminoto was initially not very enthusiastic about the emergence of Djawa Dipa, as the movement gradually expanded in 1918 and his dominance within Sarekat Islam (CSI) began to wane, he quickly moved to consolidate new forces. Djawa Dipa was then promoted and pushed to become a militant movement aimed at transforming the “slave mentality” of the Javanese people (Siraishi, 1997).

As a movement, Djawa Dipa often directly issued appeals encouraging the reduction of krama (high-level Javanese) usage. One of its early recommendations included changing honorifics or forms of address: using “Wiro” for men, “Woro” for married women, and “Liro” for unmarried women (Thamrin, 2022). The movement also expanded to include calls for rejecting long-standing gestures of deference embedded within the Dutch East Indies bureaucracy. These gestures included a wide range of social behaviors, dress codes, hierarchical language use, and honorary titles.

Javanese people were required to treat Dutch officials with elaborate forms of submission: walking in a crouched or squatting position (jongkok), addressing colonial officers as kanjeng tuan, sitting cross-legged in their presence, and performing a respectful gesture of placing both hands against the upper lip (sembah) after the officials spoke (Der Meer, 2021).

Although Djawa Dipa was enthusiastically welcomed by the Javanese public and became a topic of discussion in various newspapers at the time, its presence also brought with it the consequence of skepticism about its effectiveness in leveling the Javanese language. This view emerged from the conservative elite, who felt that their power was being threatened by the rise of Djawa Dipa. This sentiment was evident, for instance, in a column published in De Indier on April 10, 1917. The author of the piece was not clearly identified, but the tone of the writing revealed a skeptical attitude toward the presence and aims of Djawa Dipa.

”De ngoko-questie houdt de gemoederen in de inlandsche wereld nog warm. Er is bereids een vereeniging gevormd onder den naam Djawa Dipa, die het ngoko zal trachten vereheffen tot algemeene tal op Java. Wij staan er zeer sceptisch tegenover!”

(The ngoko question continues to stir emotions in the inlander. An association has already been formed under the name Djawa Dipa, which will attempt to elevate ngoko to the status of a general language in Java. We view this with great skepticism!)

There was also a lengthy opinion piece titled “Djowo Dipo Contra Adat” (“Djawa Dipa Against Custom”) written by a district head (the specific region was not detailed), published in the De Locomotief newspaper on June 14, 1921. In it, he expressed his concerns about the growing presence of Djawa Dipa, which he viewed as increasingly troubling.

According to him, the Djawa Dipa movement was seen as undermining the authority of the priyayi (Javanese aristocracy). This colonial official considered the use of informal terms like “Kowe” (you, in low-register Javanese) when addressing officials to be an insult to the established customs and power structures.

Although he did not deny that real change was happening, he insisted that politeness must remain paramount. He cited an incident in which a wedana (district head) was approached by two members of Djawa Dipa as an example of this perceived breach of decorum.

”…De wedono liet zich niettemin door die woorden niet van streek brengen, bleef kalm en vroeg den heeren gemoedelijk in het hoog-Javaansch: ‘Sampean wonten perloe poenopo?’ (Wat is er van uw dienst?”

(…The wedana, however, was not shaken by those words, remained calm, and politely asked the gentlemen in high Javanese: ‘Sampean wonten perloe poenopo?’What can I do for you?’)

Despite all of that, Djawa Dipa chose to remain actively vocal. To facilitate the wider dissemination of their propaganda, in April 1921 they finally launched the first issue of their weekly newspaper titled Hindia Dipa (Thamrin, 2022).

The release of the newspaper appears to have been accelerated compared to the original plan. This differed from a report in the Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant dated March 22, 1921, which had stated that Hindia Dipa would be published at the end of 1921.

On the other hand, Hindia Dipa, as the media outlet of Djawa Dipa, chose to use a blend of Malay-Javanese as its primary language.

Language as a revolutionary medium

During the 19th century, the Dutch systematically indoctrinated themselves into Javanese society through a process of cultural appropriation that legitimized their authority. This legitimacy was heavily dependent on the preservation of the culture of the traditional elite. The Dutch deliberately created cultural hegemony by adopting and institutionalizing Javanese-style rituals. Symbols of power—such as hierarchical forms of dress, lifestyle, language, consumption, and architecture—were carefully maintained and reinforced by the colonial regime (Der Meer, 2019).

Clifford Geertz, in his book Negara: The Theatre State in Nineteenth-Century Bali, also explained that state power is not only embodied in institutions but also in the continuous production of symbols. In other words, symbols are not merely matters of aesthetics—they are manifestations of power itself.

All of this gradually began to shift. The early 20th century marked a transformative period of social and cultural change. The Dutch Ethical Policy, though intended as a colonial reform, inadvertently created the conditions for the emergence of indigenous movements that became increasingly critical of all forms of feudal relations with the colonial power (Der Meer, 2021).

It was within this context that history records the rise of a radical movement in Surabaya that opposed state domination—particularly as it related to language hierarchy. As noted by J. P. Zurcher, although traditional customs were still respected, the times had changed significantly. The Javanese people of the past were no longer the same as those of the present. They had evolved, and with that evolution came a naturally emerging spirit of resistance.

DAFTAR PUSTAKA

Der Meer, A. (2019). Igniting Change in Colonial Indonesia: Soemarsono’s Contestation of Colonial Hegemony in a Global Context. Journal of World History, 30(4), 501–532.

Der Meer, A. (2021). Sweet Was the Dream, Bitter the Awakening: The Contested Implementation of the Ethical Policy 1901-1913. In Performing Power: Cultural Hegemony, Identity, and Resistance in Colonial Indonesia (pp. 48–76). Cornell University Press.

Districtshoofd. (1921, June 14). Djawa Dipa Contra Adat. De Locomotief.

Djawa Dipa. (1917, April 10). De Indier.

Geertz, C. (2017). Negara Teater: Kerajaan-Kerajaan di Bali Abad Kesembilan Belas. BasaBasi.

Java en Madoera. (1921, March 22). Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant .

Siraishi, T. (1997). Zaman Bergerak: Radikalisme Rakyat di Jawa 1912-1926. Pustaka Utama Grafiti.

Thamrin, M. H. (2022). Djawa Dipa: Sama Rata, Sama Rasa, Sama Bahasa 1917-1922 (1st ed.). Komunitas Bambu.

Zurcher, P. J. (1920). De Indische Gids (Vol. 42). J. H. de Bussy.

by Penelitian Arek | Jun 9, 2025 | Arek-Arek

Image 1 View of Ludruk “Marhaen”, a sketch by Legowo. Source: Harian Rakjat, 26 September 1965

Alfian Widi Santoso | Alumni History Department in Airlangga University | Associate Research in Arek Institute

In various studies on the history of Ludruk (a traditional Javanese theater form), Lekra (Lembaga Kebudayaan Rakyat, or the Institute of People’s Culture) is often portrayed as an antagonistic figure in its efforts to develop the Ludruk art form. This is illustrated in Tempo’s special edition titled “Lekra and the 1965 Upheaval”, which mentions that Lekra once conducted a cultural offensive through Ludruk performances that featured plays with titles considered offensive to religion, such as “Malaikat Kimpoi” (The Angel Marries), “Gusti Allah Ngunduh Mantu” (God Throws a Wedding), “Matine Gusti Allah” (The Death of God), and others (Tempo, 2013).

Both the book by Saskia Wieringa and Nursyahbani Katjasungkana (2020) and the special Tempo report explain that these plays were merely intended to provoke rural communities to remain critical of their land rights, especially since they were often vulnerable in legal matters. Wieringa and Katjasungkana explain that the play “Matine Gusti Allah” is a simple story about the harsh conditions faced by rural communities, and was meant to commemorate the death of Jesus Christ or Easter (Wieringa and Katjasungkana, 2020).

Ultimately, the phenomenon of controversial Lekra plays is more frequently presented in a negative light, disregarding the factual content of these performances. This issue has also given rise to a partial yet dominant historical narrative about the cultural offensive, with the most logical justification being the limitation of sources. It has also resulted in the loss of fragmented narratives about Lekra, such as the concept of “1-5-1,” one combination of which includes “Good Traditions and Revolutionary Modernity.” Despite the controversy, there were in fact many efforts initiated by Lekra in the context of traditional performing arts that are rarely narrated due to the dominance of anti-communist power structures built after 1965 and entrenched to this day through the cultural hegemony of the New Order regime.

This article aims to fill the gaps in the current narratives surrounding Lekra’s Ludruk. Moreover, it is based on relatively new archival sources that are rarely included in the dominant and problematic narratives about Lekra’s Ludruk. To date, there is only one book that utilizes these sources, namely “Lekra Tak Membakar Buku: Suara Senyap Lembar Kebudayaan Harian Rakjat 1950–1965” (Lekra Didn’t Burn Books: The Silent Voices of the Culture Section of Harian Rakjat, 1950–1965) by Muhidin M. Dahlan and Rhoma Dwi Aria Yuliantri. Even so, that book only presents very limited archival material regarding Lekra’s Ludruk.

Ludruk, Cak Durasim, and Its Revolutionary Actions

One of the most prominent narratives surrounding Cak Durasim is his resistance to Japanese fascism on stage. His iconic parikan (rhymed verses) established him as a pioneering Ludruk performer who embodied both revolutionary and populist values. His emergence cannot be separated from the culture of urban peripheries and the Arek subculture that flourished in East Java, particularly in and around Surabaya.

According to Peacock, Ludruk rarely reached the priyayi (Javanese aristocracy) and santri (Islamic religious community) groups, as various opinions rendered Ludruk controversial. Most of its audience and performers came from the proletarian class, such as street vendors, pedicab drivers, commercial sex workers (CSWs), domestic helpers, and others (Peacock 1987).

The use of coarse or ngoko (informal Javanese) language is a distinctive hallmark of both Ludruk and the Areksubculture itself. This was likely influenced by the rough contours of urban culture, which was filled with migrants seeking better livelihoods. According to Rachman (2022), the rise of the Arek subculture—especially in Surabaya—was an indirect consequence of the alienation that emerged in urban areas during Dutch colonialism (Rachman 2022).

In line with Rachman’s argument, Peacock sees Ludruk as a people’s art or proletarian art. Aside from its close ties with left-wing cultural organizations, Ludruk also emerged as a response to the social inequalities occurring in cities like Surabaya (Peacock 1987). In contrast, urban life since the colonial era was extremely unequal: Europeans lived from one societeit (social club) to another, from one café to the next (Achdian 2023), while the indigenous population lived in poorly sanitized private village ss or even squatted in abandoned buildings due to limited access to urban spaces (Basundoro 2013).

Therefore, it’s unsurprising that Ludruk emerged from humble street performances in markets and evolved into a stage art form featuring stories closely tied to the people’s everyday lives. As part of this response, Cak Durasim, a pioneer of Ludruk, was also a movement activist in the 1930s. His involvement in PBI (Persatuan Bangsa Indonesia, or the Union of the Indonesian Nation), founded by Dr. Soetomo, marked the beginning of his resistance (Rachman 2023).

During the Japanese occupation of Indonesia (1942–1945), Cak Durasim, as a Ludruk artist, resisted in the way he could—by composing satirical and provocative parikan, which later became legendary and ultimately led to his execution by the Japanese. At the same time, he was even reported to have been involved in an underground movement organized by the PKI (Indonesian Communist Party), though the nature of this underground activity remains unclear (Antariksa 2005).

Lekra and the Discourse on People’s Art

“Since its inception, Lekra has consistently unearthed the richness of people’s art across various regions—arts which, until then, could be likened to gold mines that had yet to be explored or exploited. Had Lekra not taken up this task, that gold might have remained forever buried under sand, or even disappeared without a trace.”

—Joebaar Ajoeb, “General Report of the Lekra Central Committee to the First National Congress of Lekra” (1959)

With its guiding principle that “The People are the sole creators of culture,” Joebaar Ajoeb’s statement at Lekra’s First National Congress becomes a certainty: that Lekra would always position the people as the primary source of artistic creation. This aligns with Hersri Setiawan’s statement (2022), which explains that Lekra’s goal was not to produce artists or writers per se, but to cultivate cultural awareness among the people through methods already ingrained in their lives—one of which was through traditional folk art (kesenian rakyat) (H. Setiawan 2021).

Muhidin M. Dahlan and Rhoma Dwi Aria Yuliantri (2008) further explain that cultural workers under Lekra carried out a collective mission rooted in their own awareness: to develop people’s art forms that otherwise only existed from village to village in a stagnant state, and would inevitably become marginalized and eventually disappear (Dahlan and Yuliantri 2008).

The use of people’s art became a highly feasible option because society was already more familiar with it than with modern forms such as opera, drama, choir, and others. Lekra, as a cultural actor, recognized that traditional art—originally perceived merely as entertainment—could be transformed into a medium for public consciousness. This was in line with the 1-5-1 principle: “Good traditions and revolutionary modernity.” Thus, Lekra’s cultural workers felt it necessary to establish creative institutions aimed at facilitating and organizing artistic communities already embedded in society, in order to “expand and elevate” people’s art (Dahlan and Yuliantri 2008).

In the context of traditional performing arts, for instance, there is Ludruk from East Java, which had long held characteristics of populism and organic resistance in its performances—such as the stories of Pak Sakera, Sarip Tambak Oso, and others. In fact, the very creation of Ludruk stemmed from lower-class resistance, exemplified by its pioneer, Cak Gondo Durasim, whose famous parikan voiced opposition to Japanese fascism:

“Pagupon omahe doro, melu Nippon tambah sengsoro”

(“A dovecote is the home of doves; joining the Japanese only brings more misery.”)

In the 1960s, Ludruk underwent a significant renewal, led by the leftist cultural movement such as Lekra. According to HR Minggu (People’s Daily Sunday edition), on January 31, 1965, the East Java branch of Lekra established the “Cak Durasim” Ludruk School, attended by 60 Ludruk artists from across East Java.

Another example is found in the field correspondence column of HR Minggu, which replaced the “Culture Section” (Ruang Kebudajaan) in Harian Rakjat starting in 1963. In the March 14, 1965 edition of HR Minggu, an article describes an experimental idea by M.D. Hadi, involving the creation of new wayang (shadow puppet) characters that reflect the people and are free from palace-centric hegemony. This experiment included plays rooted in the lives of common people. This aligns with Hersri Setiawan’s account during his time as head of Lekra’s Central Java branch, where the organization promoted the concept of “Fable Wayang” targeted at children, and wayang narratives grounded in the populist tradition (H. Setiawan 2021).

Lekra and Ludruk: What Has Been Done?

“Will Ludruk always be branded as cheap art and never accepted by intellectual circles?!” Thus spoke Bambangsio in his correspondence titled “The Second Lestra Surabaya Symposium: On Ludruk Drama Experiments”, published in HR Minggu, May 24, 1964. This statement aligns with the words of Gregorius Soeharsojo in his memoir, explaining his fondness for Ludruk: “I enjoy Surabaya’s Ludruk the most, with its witty rhymes that playfully jab at various issues. The wholesome humor of its comedians always sides with the common people” (Goenito, 2016).

Both Soeharsojo’s appreciation and Bambangsio’s inquiry reflect how, in the 1960s, Ludruk was no longer merely a folk performance watched only by the lower class—it was embraced across societal layers. Bambangsio noted that Ludruk was undergoing significant development at the time, attracting broader audiences. The invitation for Ludruk Marhaen to perform at the State Palace in both 1958 and 1964 was crucial evidence of this growth, marking a turning point for adapting Ludruk to its contemporary context (Harian Rakjat, 1958).

Several key moments illustrate how the leftist movement, particularly Lekra, worked to develop Ludruk as a noble tradition fused with revolutionary modernity in line with the 1-5-1 principle. The first moment, as documented in Harian Rakjat, was the participation of Ludruk Marhaen actors in the film Kunanti di Djokdja (1959). The second was the East Java Ludruk Institution Conference held from July 30 to August 1, 1964, which resolved, among other things, to support the Ministry of Education and Culture’s directive to oppose imperialist cultural penetration. The third was a series of events in 1965: Ludruk Marhaen was invited again to perform at the State Palace, the Tjak Durasim Ludruk School was founded, and the First National Ludruk Congress was held, eventually establishing the United Ludruk of Indonesia (PERLINDO).

Ludruk gained national attention through the film Kunanti di Djokdja (1959), which featured Ludruk actors. An advertisement in Harian Rakjat on June 19, 1959, claimed the film offered fresh humor while portraying the 1945 Revolution through laughter and tears. It was also touted as a major film of the year with the potential to “explode” the capital’s audience.

This marked an important experiment—integrating folk art like Ludruk with modern tools such as film. The film’s success, directed by Tan Sing Hwat, received positive responses from various audiences across Indonesia. Through cinema, many Indonesians were introduced to Ludruk, which had previously been popular mainly in East and Central Java. Additionally, the film sought to counteract the growing influences of Americanism and Indianism in Indonesia’s film industry (Harian Rakjat, 1959). The success of this experiment earned Tan Sing Hwat a Best Screenwriter award at the 1960 Indonesian Film Festival (A. Setiawan, 2019).

The film’s success inspired Ludruk artists affiliated with Lekra to participate in the modernization of folk art in line with the principle of “noble tradition and revolutionary modernity.” This was reflected in the resolutions of the first East Java Ludruk Institution Conference (July 30 – August 1, 1964), which declared that Ludruk organizations would actively oppose American imperialist films and volunteer to fill content gaps in the film industry. The 250 participating Ludruk organizations also emphasized that Ludruk should not only be humorous but also raise political awareness, combat superstition, and promote unity. At this conference, a new leadership was chosen for the East Java Ludruk Institution: J. Shamsudin (Ludruk Marhaen) as Chair, M. Nasrip as Vice Chair, and Asmirie as Secretary (Harian Rakjat, 1964).

On January 31, 1965, HR Minggu reported concrete steps taken after the East Java Ludruk Conference. One such step was the founding of the Tjak Durasim Ludruk School, aimed at advancing Ludruk as a revolutionary folk art. The school was officially opened by Shamsudin, the chair of the Ludruk Institution, and welcomed 60 Ludruk artists from various parts of East Java as its first cohort. This initiative also served to prepare for the upcoming First National Ludruk Congress scheduled for April (Harian Rakjat, 1965a).

Unfortunately, the Congress did not take place in April, likely because Ludruk Marhaen had another performance scheduled at the State Palace (Harian Rakjat, 1965). Eventually, the First National Ludruk Congress and Festival were held from July 11 to 16, 1965, at Balai Pemuda, Surabaya. Under the slogan “Strengthen the Integration of Ludruk with the People and the Revolution”, the congress was reportedly attended by 25,000 Ludruk artists, according to Harian Rakjat (Harian Rakjat, 1965a).

Topics discussed included: “The History and Development of Ludruk,” “Artistic Issues in Relation to Audience,” and “Modernization and Organization of Ludruk.” The congress produced important resolutions aimed at advancing Ludruk as revolutionary folk art aligned with Sukarno’s political agenda, including:

- Ludruk must foster a national culture serving workers, farmers, fishermen, and soldiers.

- Form a centralized Ludruk organization called United Ludruk of Indonesia (PELINDO).

- Implement necessary reforms to enhance its commitment to the people and revolution, while continuing its revolutionary tradition.

- Focus on education to improve Ludruk’s ideological and artistic quality.

- Declare Tjak Gondo Durasim a national Ludruk hero.

- Ensure Ludruk artists integrate with the people and the revolution.

- Host Ludruk festivals to encourage growth.

- Promote cultural cooperation with state apparatus in line with revolutionary character (Harian Rakjat, 1965c).

The Congress also discussed writing a history of Ludruk and artistic experimentation. These efforts demonstrated Lekra’s approach to developing regional culture. As M.H. Lukman, Vice Chair I of the PKI Central Committee, stated:

“The idea that revolutionizing regional drama would harm its popularity is not only inaccurate but has already been refuted by revolutionary drama artists. Precisely through renewal and technical enhancement rooted in tradition, revolutionary artists have shown that regional drama can achieve higher ideological and artistic quality while gaining broader appeal” (Harian Rakjat, 1965b).

Following the congress, a Ludruk Performance Week Festival was held, in which Ludruk organizations from various regions performed and were judged. The festival winners were: Ludruk “Arumdalu” from Jombang (1st), Ludruk CGMI Surabaya (2nd), and Ludruk Sidoarjo (3rd). Honorable mentions included teams from Kudus, Jember, Blitar, “Mawar Merah” from Rembang, and Lamongan (Harian Rakjat, 1965d).

After the congress and festival, PERLINDO, the umbrella organization for Ludruk, began working. The only announcement published in Harian Rakjat (September 12, 1965) urged all member organizations to study Sukarno’s Takari speech. PERLINDO reminded its members:

“Our attitude toward both traditional and foreign cultures must be the attitude of the national democratic revolution: we strip feudalism from the old culture and eradicate imperialism from foreign cultures” (Harian Rakjat, 1965e).

Tragically, the 1965–1966 catastrophe struck. Cultural activities were paralyzed, including Ludruk. All performances were banned for two to three years, according to Cak Kartolo (Harian Rakjat, 1965). In the aftermath, Ludruk organizations were often brought under military institutions. Under the New Order regime, Ludruk became a propaganda tool and lost the revolutionary spirit of Tjak Gondo Durasim, who had once fought fiercely against oppression.

References

Achdian, Andi. 2023. Ras, Kelas, Bangsa: Politik Pergerakan Antikolonial di Surabaya Abad Ke-20. Tangerang: Marjin Kiri.

Antariksa. 2005. Tuan Tanah Kawin Muda: Hubungan Seni Rupa dan Lekra 1950-1965. Yogyakarta: Yayasan Seni Cemeti.

Basundoro, Purnawan. 2013. Merebut Ruang Kota: Aksi Rakyat Miskin Kota Surabaya 1900-1960an. Tangerang: Marjin Kiri.

Dahlan, M. Muhidin, dan Rhoma Dwi Aria Yuliantri. 2008. Lekra Tak Membakar Buku: Suara Senyap Lembaran Kebudayaan Harian Rakjat 1950-1965. Yogyakarta: Merakesumba.

Dokumen (I): Kongres Nasional Pertama Lembaga Kebudajaan Rakjat. 1959. Bagian Penerbitan Lembaga Kebudajaan Rakjat.

Goenito, Gregorius Soeharsojo. 2016. Tiada Jalan Bertabur Bunga: Memoar Pulau Buru dalam Sketsa. Yogyakarta: Insist Press.

Harian Rakjat. 1958. “Marhaen DI ISTANA,” 12 April 1958.

Harian Rakjat. ———. 1959a. “Adv. Kunanti di Djokdja,” 19 Juni 1959.

Harian Rakjat. ———. 1959b. “Film Ludruk KUNANTI DI DJOKDJA: Peranan wanita dilakukan oleh para pria,” 20 Juni 1959.

Harian Rakjat. ———. 1965a. “Sekolah Ludruk ‘Tjak Durasim’ Surabaja,” 31 Januari 1965.

Harian Rakjat. ———. 1965b. “Kongres Nasional Ludruk,” 7 Maret 1965.

Harian Rakjat. ———. 1965c. “Wkl. WALIKOTA SURABAJA PADA KONGRES LUDRUK : Kobarkan terus semangat Tjak Durasim,” 18 Juli 1965.

Harian Rakjat. ———. 1965d. “KONGRES NASIONAL KE-I LUDRUK SUKSES: NASAKOMKAN RRI-TV SELURUH INDONESIA,” 25 Juli 1965.

Harian Rakjat. ———. 1965e. “DPP PERLINDO: DENGAN TAKARI DJADIKAN LUDRUK DUTA MASA DAN DUTA MASSA,” 12 September 1965.

Harian Rakjat . 1965. “Ludruk Marhaen di ibukota,” 28 Maret 1965.

Harian Rakjat. 1964. “KONF. LEMBAGA LUDRUK DJATIM: Bubarkan Ampai, Ritul DFI,” 9 Agustus 1964.

Harian Rakjat. ———. 1965a. “Kongres Nasional LUDRUK dibuka hari ini,” 11 Juli 1965.

Harian Rakjat. ———. 1965b. “M.H. LUKMAN: Dengan semangat Tjak Durasim kobarkan ofensif revolusioner dibidang ludruk,” 13 Juli 1965.

Harian Rakjat. ———. 1965c. “Meningkatkan Ludruk atas dasar tradisi revolusionernja,” 22 Agustus 1965.

Peacock, James L. 1987. Rites of Modernization: Symbolic and Social Aspects of Indonesian Proletarian Drama. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Rachman, Anugrah Yulianto. 2022. “Kemunculan Kota, Kemunculan Arek Surabaya.” Arek Institute. 8 Januari 2022. https://www.arekinstitute.id/blog/2022/01/08/kemunculan-kota-kemunculan-arek-surabaya/.

———. 2023. “Durasim (1).” Arek Institute. 26 Desember 2023. https://www.arekinstitute.id/blog/2023/12/26/durasim-1/.

Setiawan, Andri. 2019. “Riwayat Tan Sing Hwat.” Historia. 11 September 2019.

Setiawan, Hersri. 2021. Dari Dunia yang Dikepung Jangan dan Harus: Kumpulan Surat, Esai, dan Makalah. Yogyakarta: Sekolah mBROSOT & Kunci Forum dan Kolektif Belajar.

Tempo. 2013. Lekra dan Geger 1965. Tempo. Jakarta: Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia.

Wieringa, Saskia E., dan Nursyahbani Katjasungkana. 2020. Propaganda & Genosida di Indonesia: Sejarah Rekayasa Hantu 1965. Disunting oleh Rahmat Edi Sutanto. 1 ed. Depok: Komunitas Bambu.

by Penelitian Arek | Feb 13, 2025 | Arek-Arek

Diky K. Arief | A student of Islamic Theology and Philosophy at the State Islamic University of Surabaya[]

When East Javanese traditional art is discussed, the main spotlight often falls on Ludruk—a performing art that has long been a cultural pride of the arek-arek (young people) community. However, behind the vibrant discussions about Ludruk, there is one crucial element that is often overlooked by the media and cultural discourse: Jula Juli. Without Jula Juli, Ludruk would not feel complete.

Jula Juli is not merely a part of the East Javanese kidungan (traditional sung poetry); it is a literary form that records the long history of its people. Within each song performed, there are narratives about anxiety, hope, humor, social criticism, and the daily lives of Javanese society, particularly in Surabaya and the broader Arek subculture regions.

Varieties of Jula Juli

Jula Juli and Ludruk are always intertwined with traditional art in East Java. As part of a Ludruk performance, Jula Juli serves as an introduction or accompaniment that breathes life into the show. However, Jula Juli does not entirely depend on Ludruk as its medium. As an independent art form, Jula Juli can be performed outside of Ludruk shows.

To trace the connection between Jula Juli and Ludruk, let us briefly explore its historical emergence. There are several versions of how Ludruk and Jula Juli originated. One story states that Ludruk was initially created by a farmer named Santik from Ceweng Village, Diwek District, Jombang Regency. In 1907, Santik, along with his two friends, Pono and Amir, performed Jula Juli from one hamlet to another while wearing makeup resembling women, which they found amusing. They then sang Jula Juli in a humorous style to entertain the public (Ismail, 2023).

Another story claims that Ludruk had already developed as early as 1890, but it was not introduced by Santik. Instead, a street performer named Gangsar from Pandan Village, Jombang, was credited with its emergence. His story closely resembles Santik’s role in pioneering Ludruk, which at the time still took the form of Lerok. According to the tale, Gangsar and his friends were performing when they encountered a crying baby being held by a man. Upon closer observation, the man had adorned himself like a woman, hoping to deceive his child into thinking they were being cradled by their mother. Inspired by this, Gangsar and his friends began performing with makeup that made them look like women. This story is also considered one of the key reasons behind the emergence of the travesti (cross-dressing) tradition in Ludruk performances (Soenarno, 2023). The final version suggests that Ludruk began to develop in Surabaya.

Unfortunately, these stories focus solely on the origins of Ludruk, while the emergence of Jula Juli remains largely undocumented. However, the development of Jula Juli has always been closely linked to Ludruk. Over time, Jula Juli started to expand its reach, evolving into an independent art form separate from Ludruk. In Jula Juli, the sung poetry follows a pattern similar to pantun (traditional rhymed verses), delivered with vocal techniques and accompanied by gending (traditional Javanese music). The narration is presented in the rough, colloquial ngoko dialect of East Javanese speech.

Regional Variations of Jula Juli

As Jula Juli evolved, it developed unique regional characteristics across East Java, adapting to the socio-cultural contexts of different communities. These variations include Jula Juli styles from Surabaya, Pandalungan, Jombang, and Malang (Setiawan, 2017). While all these variations retain similar musical patterns and accompaniment styles, each version presents a distinct atmosphere and character, particularly in linguistic aspects.

The diversity of Jula Juli has given rise to its own historical narratives in different regions. It reflects the cultural, social, and political conditions of its time. For example, in Jombang, a Jula Juli style developed using the slendro Pathet Wolu scale. This scale was performed during Bapang Wayang Topeng Jatiduwur performances (Annur, 2022). However, there is neither historical evidence nor folklore detailing the origins of Jula Juli in the slendro Pathet Wolu scale. Nevertheless, Wayang Topeng Jatiduwur has existed since the Majapahit era during King Hayam Wuruk’s reign and was later revitalized by Ki Purwo in Jatiduwur Village, Kesamben, Jombang.

Beyond Jombang, around 2014 in Malang, a new musical style emerged under the name Jula Juli Lantaran Gaya Malang. This style was pioneered by Sumantri, who created it in response to the limitations of previous macapat song styles (Pamuji, 2017). The distinction lies in its musical characteristics: Jula Juli Lantaran Gaya Malang incorporates elements of macapat with rhythmic arrangements highlighting Kendang Kalih and Gambayak drumming techniques (Pamuji, 2017). This marks a unique feature not found in conventional Jula Julicompositions.

Unlike the Malangan or Jombangan styles, Jula Juli Madura has a history closely tied to the socio-political dynamics of the Dutch colonial era. This version of Jula Juli was born as a product of its time, shaped by the cultural assimilation between Madurese and Javanese communities under Dutch colonial racial policies. The Dutch anthropologist Huub de Jonge documented colonial-era stereotypes about the Madurese people, portraying them as “backward” and “harsh-tempered”—both of which reflect colonial biases. This narrative reinforced the discriminatory perspectives of colonial rule, further stigmatizing the Madurese in the eyes of both the colonizers and surrounding Javanese communities.

The presence of the Madurese people was often positioned as “the other.” Their voices remained faintly heard. This historical backdrop of stereotyping led Jula Juli Madura to become a unique form of resistance against systematic subjugation by colonial systems and knowledge structures (Setiawan, 2017).

This defiance is also reflected in kèjhungan gending Yang-Layang, a distinctive kidungan (sung poetry) from Madura influenced by Javanese kidungan and the adaptive evolution of Jula Juli. However, its uniqueness lies in its high-pitched and melancholic cengkok(melodic ornaments), symbolizing the Madurese people’s strong sense of dignity, outspokenness, and migratory nature (Mistortoify, 2015). One example of kèjhungan Yang Layang is as follows:

“Sampang roma sakè translation: Sampang (has) hospital

Tuan dokter acapèngan potè The doctor wears white hat

Lo’ ghãmpang dhãddhi rèng lakè’ It is not easy to be a man

Mon lo’ pènter nyarè pèssè” If cannot earn money

(Mistortoify, 2015)

Through the Jula Juli they created, they not only expressed their cultural identity but also demonstrated resistance against the stereotypes that had long been imposed upon them.

The migration of the Madurese people to the Tapal Kuda (Horseshoe) region also gave rise to a unique Jula Juli style known as Pandalungan. Pandalungan refers to Madurese communities born in Java who have assimilated with Javanese culture while living in the Tapal Kuda region, which includes Jember, Situbondo, Probolinggo, and Lumajang (Satrio, 2020).

This migration can be traced back to the 18th century, specifically in 1870, when the Dutch colonial government enacted more agrarian policies that allowed private enterprises to expand their economic activities in East Java. As a result, rubber, sugarcane, and tobacco plantations began to emerge, and low-wage laborers were brought in from Madura to work on them (Akhiyat, 2023). However, this was nothing more than a colonial strategy to perpetuate slavery. The Dutch forcibly employed enslaved laborers on plantations—bringing slaves from Java to work on land in Sumatra and from Madura to work on land in Java. By sourcing enslaved workers from regions separated by the sea, they ensured easier control over them (Setiawan, 2017).

As a result, cultural assimilation occurred in the inclusive Tapal Kuda region, giving birth to distinctive traditions—one of which is Jula Juli Pandalungan/Pendalungan. This particular Jula Juli is often performed in Jaran Kencak (a traditional horse dance) performances and is incorporated into the Napel/Sumpingan segment. In this segment, a guest sings Jula Juli to the host while presenting monetary offerings (saweran) to the Remo dancer as a gesture of respect to the host (Juwariyah, 2023).

In her writings, Nura Murti compiled Jula Juli/kèjhungan from the Pandalungan tradition in Jember Regency, highlighting the values of cultural assimilation in the Tapal Kuda region (Murti, 2017), such as the following example:

“Tanem magik tombu sokon terjemahan: planting Tamarind grows breadfruit

tabing kerrep benyyak kalana A tightly woven bamboo was full of scorpions

mompong gik odik koddhu parokon As long as one is alive, harmony must be maintained

ma’ olle salamet tèngka salana” To stay safe in one’s behaviour

The various types of Jula Juli demonstrate that music and culture are not merely forms of entertainment but also serve as tools for expressing identity, worldview, and even dissatisfaction with prevailing social conditions. Like other traditional arts, Jula Juli stands as a silent witness to how culture becomes an arena of struggle—where narratives of oppression can be transformed into songs that inspire and unite people from diverse walks of life.

Jula Juli as a Medium of Social Resistance and Propaganda

During the colonial period, Jula Juli evolved into a medium for criticizing the Japanese colonial system, infused with elements of satire. For example, in one of the most renowned kidungan (traditional sung poetry) pieces by Cak Durasim, sharp criticism was directed at Japanese rule, which had further worsened the conditions of the indigenous people, as cited in Setiawan’s (2021) article:

“A dovecote is a home for doves,

Following the Japanese only brings suffering.

Bought klepon at the station,

Following the Japanese means no pension.”

The first two lines of the verse are also inscribed on Cak Durasim’s tombstone at Tembok Gede Cemetery in Surabaya, serving as a lasting reminder that local arts and culture—such as Ludruk and Jula Juli—have functioned as tools of resistance. Jula Juli was not merely an art form; it was a means of challenging the status quo of its time.

Beyond being a vehicle for social criticism, Jula Juli was also used as a medium for propaganda. During the Guided Democracy era of the late 1950s, political parties frequently utilized this art form to convey ideological messages from various political groups. This is evident from the fact that many political parties had autonomous cultural organizations within them. Some of these included the Indonesian National Party (PNI) with its National Cultural Institute (Lembaga Kebudayaan Nasional—LKN), the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) with its People’s Cultural Institute (Lembaga Kebudayaan Rakyat—Lekra), Masyumi with its Islamic Arts and Culture Association (Himpunan Seni Budaya Islam—HSBI), and the Catholic Party with its Catholic Indonesian Cultural Institute (Lembaga Kebudayaan Indonesia Katolik—LKIK) (Susanto, 2017).

The presence of multiple political streams and ideologies made culture an arena for ideological battles and influence. Art and literature, as part of culture, were often used as mediums to convey ideological messages, either explicitly or implicitly. This even led to the notion that “whoever wins has the right to write history” (Susanto, 2017).

This was no exception for Jula Juli and Ludruk. The proliferation of Ludruk groups in East Java turned the art form into a political battleground, resulting in the emergence of two major factions: Ludruk supporting the PKI and Ludruk supporting the PNI. When these two factions performed on neighboring stages, it was not uncommon for them to engage in ideological duels through Jula Juli performances (Setiawan, 2021).

“Budal tandur, muleh njaluk mangan “Jumat legi nyang pasar genteng

Godonge sawi, dibungkus dadi siji Tuku apel nang Wonokromo

Ayo dulur, podho bebarengan Merah putih kepala banteng

Nyoblos partai, partai PKI” Genderane dr. Soetomo”

That Jula Juli verse is one example of how traditional art was utilized by political parties to subtly convey their ideological messages. With its colloquial language and a rhythm familiar to the people of East Java, political propaganda was woven into the lyrics of the kidungan(chant). In this way, Jula Juli transformed into an effective political communication tool, reaching various segments of society that might not be accustomed to formal political narratives. However, kidungan and Ludruk performances associated with the PKI began to fade following the events of September 30. That incident marked a period of silence and the disappearance of Ludruk from the national stage (Setiawan, 2021).

At that time, the New Order regime did not only suppress the PKI physically but also sought to dominate culture associated with it. The Pengkhianatan G30S/PKI (The Treachery of G30S/PKI) film, produced by the regime, was widely disseminated, books deemed to contain leftist ideology were banned and removed from circulation, and traditional arts were tamed by the regime to steer literature toward “safe” storytelling (Restu, 2020). One of the affected art forms was Ludruk. As a form of folk art closely tied to narratives of the people and resistance, Ludruk was considered dangerous. During that era, both Ludruk and Jula Juli, as part of Ludruk, temporarily lost their voices.

The Revitalization of Jula Juli in the Contemporary Era

Amid the influence of both Western and Eastern cultures today, this tradition faces the challenge of staying relevant in an era of modernization. The name Cak Kartolo, a legendary Ludruk Suroboyoan maestro, is often credited with playing a significant role in revitalizing Jula Juli, ensuring its survival and acceptance by modern audiences.

Cak Kartolo recorded his Ludruk performances on cassette tapes, which were then widely distributed across East Java. He became well-known for delivering Jula Juli with a comedic style rich in humor. In every recording, he was always accompanied by the karawitan(traditional Javanese musical ensemble) group Sawunggaling (Mukaromah, 2018).

Apart from Sawunggaling with Cak Kartolo, during the same period, Cak Sulabi and his Ludruk group Budhi Wijaya also gained recognition for their popular Jula Juli Suroboyoan, such as the following Jula Juli:

“Mulone jok gampang dulur peno dipecah belah

mundhakno sing seneng kaum penjajah

sopo sing salah dulur kudu podo ngalah

supoyo persatuan kito gak gampang blubrah”

Moreover, Jula Juli continues to reinvent itself by addressing more contemporary issues. For example, in the field of education, Jula Juli is used to teach moral values, history, and even social skills. One such example is the following kidungan:

“Sugeng enjang salam literasi

Anak-anakku sayang kabeh sing tresnani

Ayo belajar gawe mbangun negeri

Iki wawasan tekan sekolah yo dipelajari (Primaniarta, 2022).”

Through Jula Juli, this art form not only reintroduces East Javanese cultural identity to the younger generation but also serves as a medium for character building and fostering social awareness. Therefore, tracing the values and knowledge embedded within Jula Juli can be seen as a form of cultural archaeology within the subculture of East Java.

References

Ismail dan Asih Widiarti, “Pentas Ludruk yang Menolak Mati,” TEMPO Publishing, 2023.

Aris Setiawan, Suyanto Suyanto, dan Wisma Nugraha Ch. R., “Jula-Juli Pandalungan dan Surabayan Ekspresi Budaya Jawa-Madura dan Jawa Kota,” Resital: Jurnal Seni Pertunjukan 18, no. 1 (2017): 1–12

Aris Setiawan, “Kidungan Jula-juli in East Java: Media of Criticism and Propaganda (From The Japanese Occupation Era to The Reform Order in Indonesia),” Harmonia: Journal of Arts Research and Education 21, no. 1 (7 Juni 2021): 79–90.

Muhammad Akbar Darojat Restu Putra, “Membaca Lagi ‘Kekerasan Budaya,’” Islam Bergerak (blog), 2020

Gita Primaniarta dan Heru Subrata, “Development of Kidung Jula-Juli as a media for children’s literacy,” Premiere Educandum : Jurnal Pendidikan Dasar dan Pembelajaran 12, no. 2 (2022): 1–13

Bima Atyaasin Annur, Setyo Yanuartuti, dan I. Nengah Mariasa, “Characteristics of Gending Jula-Juli Laras Slendro Pathet Wolu in The Bapang Dance Jombang Jatiduwur Mask Puppet,” Virtuoso: Jurnal Pengkajian dan Penciptaan Musik 5, no. 2 (2022): 142–47.

Iska Aditya Pamuji, “GARAP GENDING JULA-JULI LANTARAN GAYA MALANG,” KETEG: Jurnal Pengetahuan, Pemikiran, dan Kajian Tentang “Bunyi” 17, no. 2 (2017): 69–79.

Sonarno, Sejarah Ludruk (Semarang: Mutiara Aksara, 2023.).

Anik Juwariyah, “The Study of Panji Culture in the Pandalungan Sub-ethnic, East Java Review: Jaran Kencak Performing Art,” Atlantis Press, 2023.

Dwi Susanto, Lekra VS Manikebu (Sejarah Sastra Indonesia periode 1950- 1965) (Yogyakarta: CAPS (Center for Academic Publishing Service), 2017).

Axzella Raudha Mukaromah, “Proses Kreatif Cak Kartolo dalam Jula-Juli” (skripsi, Yogyakarta, Institut Seni Indonesia Yogyakarta, 2018).

Prakrisno Satrio, Suryanto Suryanto, dan Bagong Suyanto, “MASYARAKAT PENDALUNGAN (Sekilas Akulturasi Budaya di Daerah ‘Tapal Kuda’ Jawa Timur),” Jurnal Neo Societal 5, no. 4 (2020): 440–49.

Akhiyat dan Amin Fadlillah, “SEEKING THE HISTORY OF PENDALUNGAN CULTURE: A DISTINCTIVE STUDY OF LOCAL CULTURAL HISTORY IN THE HISTORY AND ISLAMIC CIVILIZATION PROGRAM OF UIN KHAS JEMBER,” Jurnal As-Salam 7, no. 2 (22 Juli 2023): 276–99.

Zulkarnain Mistortoify, “ONG-KLAONGAN DAN LÈ-KALÈLLÈAN ESTETIKA KÈJHUNGAN ORANG MADURA BARAT” (Yogyakarta, Universitas Gadjah Mada, 2015).

Fitri Nura Murti, “Pandangan Hidup Etnis Madura dalam Kèjhung Paparèghân,” Istawa : Jurnal Pendidikan Islam 2, no. 2 (2017).

by Penelitian Arek | Dec 6, 2024 | Arek-Arek

Cak Durasim and his Ludruk troupe frequently appeared on radio broadcasts starting around 1939, and they began gaining national fame through their Ludruk performances broadcasted nationwide, thanks to their plays and comedy sketches that resonated with the public. The Surabayan-style humor became a hallmark of the Ludruk Durasim group. However, in its early days, as noted in a report from the magazine Soeara Niroem, creating playwright scripts was quite challenging. Despite this, they successfully drew upon literary works published by Balai Pustaka and found inspiration from their surroundings as their main sources (Soeara Nirom 1939). On the other hand, activities before the 1939 period were less associated with radio broadcasts, as recorded in Soeara Niroem.

The year 1929 marked the earliest recorded performances of Cak Durasim’s Ludruk group, and he did not perform alone but collaborated with other troupes, such as the Genteng Ludruk troupe (Swara Publiek 1929). Their performances in Gresik were not a one-time event; rather, Durasim and his Ludruk group held several shows there (De Indische Courant 1938). Night markets played a significant role in the Ludruk troupe journey of Cak Durasim. In Surabaya, two night market locations were mentioned: the Surabaya Night Market (Jaarmarkt) and the National Night Market (Panjebar Semangat 1935; Soeara ’Oemoem 1937). The local residents of Surabaya eagerly welcomed these performances, flocking to the venues because they found the humor both entertaining and deeply moving (Panjebar Semangat 1938a).

The Indonesian National Building (G.N.I.) was abuzz with participants debating the validity of information in an article published by the Soeara Oemoem newspaper titled “The Difference Between Mecca and Digoel.” Among the 3,500 attendees were Arab individuals; the situation became so chaotic that the police almost dispersed the event. Later that evening, the commotion grew even louder. Then, Cak Durasim appeared at the entrance, and the debate participants warmly welcomed him, inviting him to join the discussion session (Bintang Timoer 1930). This news from Bintang Timoer about the public debate at G.N.I. highlights Durasim’s involvement in public discourse.

In addition to nationalist/anti-colonial activities organized by indigenous groups, G.N.I. also served as a cultural hub, hosting performances such as wayang orang (traditional Javanese theater). However, by around 1937, cultural activities and performances at G.N.I. had dwindled, leaving the venue eerily quiet. To revive the atmosphere, Durasim and his Ludruk group took the initiative to bring the G.N.I. back to life. Their efforts successfully drew in many local residents, who thoroughly enjoyed the performances by Durasim and his group. The lively atmosphere prompted G.N.I. management to plan regular Ludruk performances every night (Soeara Oemoem 1937).

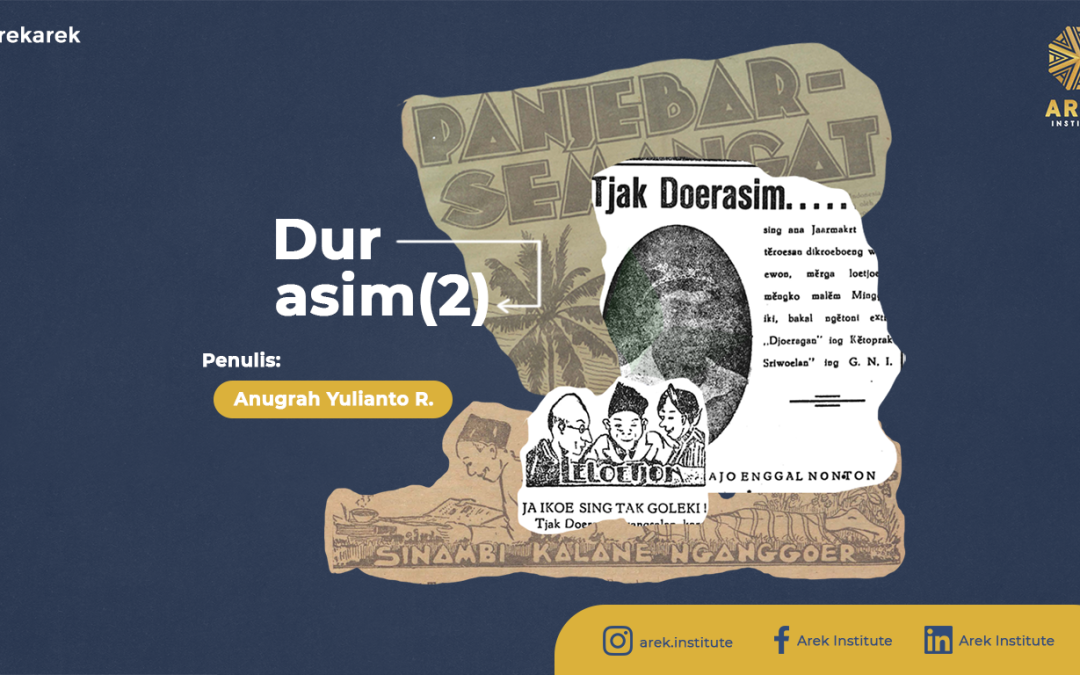

Durasim’s artistic activities were frequently documented in local newspapers between 1929 and 1938. Key nodes of Durasim’s movements and artistic pursuits were spread across several locations, such as the Surabaya Night Market (Jaarmarkt), Gresik Night Market, National Night Market, Grogol village, and G.N.I. Grogol village in Surabaya was a regular venue for his performances, held nightly at 8 PM with a variety of cultural and artistic activities (Sin Tit Po 1931). Both Ludruk performances and public debates were historically recorded, providing archival evidence of Durasim’s legacy. Unlike the later Durasim (1) article, which focused on his radio broadcasts, his activities before 1939 were predominantly live performances. This period marked a crucial phase in the early development of Ludruk art, as numerous plays and comedic sketches were documented in the Panjebar Semangat newspaper between 1935 and 1938.

Panjebar Semangat: Documenting the Early Development of Ludruk

Fragments of plays and comedic sketches from the early development of Ludruk are scattered throughout the columns of Panjebar Semangat. Several key columns recorded these fragments, marking significant historical notes in the evolution of Ludruk art. Among the notable columns featuring Ludruk plays and sketches from this early period are Leloetjon and Sinambi Kalane Nganggoer (Panjebar Semangat 1935a). This Javanese-language newspaper, written in a mix of informal and refined styles (ngoko-alus), provides historical evidence of the discourse surrounding Ludruk performances.

The Sinambi Kalane Nganggoer column often presented Ludruk plays in script form, with recurring names such as Cak Durasim, Seboel, Man Djamino, Tjak Besoet (read: Cak Besut), Santinet, and Siti Asmoenah frequently appearing in its content (Panjebar Semangat 1935a, 1938c, 1938b). These six figures consistently surfaced in both conversations and Ludruk play scripts.

The plays featured in Sinambi Kalane Nganggoer employed a range of linguistic styles and tackled contemporary issues of the time. Dutch, for instance, was often used to refer to government office terminology and metaphors in the scripts of Ludruk performances during this period. Furthermore, popular issues of the era were sometimes incorporated into the scripts. One example is a play titled Darmawisata, which depicted a comparison of the vacation habits of Javanese aristocrats (priyayi) and Americans.

“Wong-wong ing Amerika jen nganakake darmawisata malah nganti ngideri donja, ndeleng kaendahaning boewana… (Panjebar Semangat 1937)”

(people in America go on excursions that take them around the world, exploring the beauty of the earth…)

In this play, the white collar priyayi class is compared to Americans. Their busy lives in office jobs needed to be balanced with vacations to refresh both body and mind. The narrative in this play script reflects the worldview of the priyayi class, closely tied to the movement led by Dr. Soetomo, which also represented the emerging priyayi class (Frederick 1989).

Cak Durasim and his Ludruk group had a strong connection with nationalist movements centered at the G.N.I., such as Dr. Soetomo’s initiatives. This relationship highlighted a consolidation between artistic and political activities during the early development of Ludruk art. Cak Durasim frequently engaged with study clubs and the Panjebar Semangat newspaper, founded by Dr. Soetomo (Cohen 2016). The close ties between Durasim and nationalist movements significantly influenced the narratives he created for Ludruk. This is evident from the numerous fragments of comedic sketches, plays, artistic activities, and Durasim’s political involvement at G.N.I. during 1929-1938. However, during this period, Durasim’s plays and sketches did not yet carry anti-colonial or resistance themes; they primarily responded to everyday phenomena or drew inspiration from Balai Pustaka’s fictional works.

On the one hand, Durasim became renowned for his death during the Japanese colonial era due to his satirical works. On the other hand, during the Dutch colonial period, global culture, including Dutch idioms and world issues, intertwined with the essence of Ludruk art. As an art form, Ludruk was a product of its time, deeply connected to the historical context of the Dutch and Japanese colonial periods. Before his death, Durasim continued to develop new forms of art, rooted in the traditions of Lerok and Besut performances (Supriyanto 2018). Residues of Besut traditions can still be seen in the dialogues appearing in Panjebar Semangat newspapers, including characters like Besut, Djamino, and Asmunah. Even the iconic red fez of Besut was noted in several historical descriptions of Cak Durasim (Cohen 2016).

To summarise, Durasim’s activities were deeply intertwined with the nationalist and anti-colonial movements during Dr. Soetomo’s era, as recorded in historical fragments and newspaper columns. The early development of Ludruk art during this period was marked by live performances (nobong) and Durasim’s political engagements at G.N.I. The years 1929-1938 represent a formative phase in Ludruk’s narrative development.

Bibliography

Bintang Timoer. 1930. “Openbare Debat vergadering Gadoeh Dan Dibubarkan.” Bintang Timoer, August 28.

Cohen, Matthew Isaac. 2016. Inventing the Performing Arts: Modernity and Tradition in Colonial Indonesia.

Frederick, William H. 1989. Pandangan Dan Gejolak Masyarakat Kota Dan Lahirnya Revolusi Indonesia (Surabaya 1926-1946). Jakarta: Gramedia.

De Indische Courant. 1938. “Kermis-genoegens.” De Indische Courant, August 6, 4.

Panjebar Semangat. 1935a. “Ja Ikoe Sing Tak Goleki!” Panjebar Semangat, December 7, 10.

Panjebar Semangat. 1935b. “Tjak Doerasim….!” Panjebar Semangat, October 26, 16.

Panjebar Semangat. 1937. “Darmawisata.” Panjebar Semangat, December 18, 15.

Panjebar Semangat. 1938a. “Iki lo gambare tjak Doerasim…” Panjebar Semangat, October 1.

Panjebar Semangat. 1938b. “Pangoepadjiwa.” Panjebar Semangat, March 26, 15.

Panjebar Semangat. 1938c. “Selingan.” Panjebar Semangat, January 8, 15.

Sin Tit Po. 1931. “Bantoean Pada Gedong Nasional.” Sin Tit Po, August 28, 1.

Soeara Nirom. 1939. “–Loedroek Tjak Doerasim–Soerabaia. Lakon: ,,Pengaroehnja Senjoeman”.” Soeara Nirom, August 1.

Soeara ’Oemoem. 1937. “Doerasim teroes main.” Soeara Oemoem, July 13, 2.

Soeara Oemoem. 1937. “Loedroek Doerasim.” Soeara ’Oemoem, April 6.

Supriyanto, Henri. 2018. Ludruk Jawa Timur Dalam Pusaran Zaman. Malang: Beranda Kelompok Intrans Publishing.

Swara Publiek. 1929. “Harga Melawan.” Swara Publiek, March 19.

by Penelitian Arek | Sep 4, 2024 | Arek-Arek

At the end of the 19th century, Malay opera and stambul comedy were held almost non-stop in the northern corner of Surabaya. French and Italian opera actors, American magicians, British circus performers, and acrobat players from Japan and Australia were brought to Surabaya via Tanjung Perak Port. The traveling show- men stopped in almost every port of the world that was opened, and were hastily polished by colonial desires. They were brought in to entertain and delight people who were said to come from the “first world”, in a place that is nicknamed arbitrarily as the “third world”.

At the same time, an operator of a motion picture screening program was among the artists of the show. The operator did not take his eyes off a large wooden box that contained projector equipment, so as not to be confused with the equipment of the performing artists on the same boat. He was not involved in “acrobatic” conversations with performance artists, but he knew that the new medium that he brought would disrupt the established show business and classic entertainment. Once the operator stepped on the harbor, he already knew where he was going to do his first screening program. The difference was, he did not even comb the small towns and remote villages as did the traveling artists. The operator only stopped at big cities that were ready for the arrival of the new medium he carried.

He was Louis Talbott, a French photographer who obtained permission from the colonial government to do the first commercially motion picture screening in Surabaya in the mid to late April 1897. He conducted a screening program at the Surabaya Theater (Schouwburg) building located in a European residential area in Surabaya. The luxurious theater, that was built at a cost of 55 thousand gulden, was the only building that already had a motion picture player.

The Talbott screening program began by playing a documentary about European merchant ships that landed in the Dutch East Indies, where one of the scenes in the film was believed to be recorded by Georges Méliès–a stage magician and illusionist from France who was just beginning to try another fortune in his career as a filmmaker. The program continued with the screening of documentary films made by Talbott himself while traveling around Java and Sumatra in October 1896, or only ten months’ difference since the Lumierre Brothers released the world’s first commercial film screening on December 28, 1895 in France.

Talbott’s premiere was successful. The definition of performance art began to falter, the stiff face of Surabaya also began to change. Compared to the famous cosmo- politan and “government seat” Batavia, Surabaya was only known as a trading city and a Dutch military base. One of the things that made us pause when condemning the Dutch colonial occupation was, perhaps, because Tanjung Perak Port turned out not only to act as gateway that takes away the most lucrative commodities from the archipelago to be sold with almost unlimited accumulated value in other parts of the world. Tanjung Perak–as a port that is loyal to anyone who wants to take anchor to sail or to anyone who wants to lean on it–is also an entry point for human achievements from other parts of the world; the entry of moving image recording and player technology made Surabaya one of the cities that became the initial location for the screening of moving images in Asia.

Shortly after the premiere at the Surabaya Theater, other screenings building began to appear. A Chinese gemstone entrepreneur in the Kapasan Market made a screening building named Kenotograph. Surabaya Theater may be proud of luxury buildings, qualified lighting, and smooth air circulation, but Kenotograph confidently offers other things: new furniture and variations in ticket prices. If Surabaya Theater had a fix rates at 1 gulden, Kenotograph was only half; there was even a choice of 25 cents for third-class seats.

Watching motion pictures became a new activity. The elites of the colonial government, aristocrats, local priyayi and Asian immigrants in Surabaya began to love this new klangenan (hobby). Outside the theater, they were amazed by the movie projector made by the Lumiere Brothers (cinematographe) that were able to produce vivid images after being projected onto a screen. “We are not disappointed, and really enjoy what we see inside,” one of the viewers told the December 23, 1909 edition of the Soerabaijasch Handelblad newspaper. The audience did not fully understand, but the experience of watching moving (or live) pictures provided an opportunity to guess the times which continually make civilization shocks–such as the presence of a printing press that contributed to the spread of ideas about political entities. People who did not get or were not allowed to watch in the theater because they came from a low social class began to grumble. Screening venues outside the luxurious theater began to be initiated by Chinese and Indian businessmen who saw the economic opportunities of this lucrative entertainment business. The screening place was not only about the building; canvas and bamboo tents for screening began to be made. The radical change to the screening venue was a response to circumventing the space which in fact had an effect on urban planning, transportation, and taxes for public entertainment during the colonial period.

We further knew that the film Talbott brought had become a marker of the times. He entered from the port of a big city called Surabaya, breaking down the chain of events ranging from the production of motion picture player technology in the middle of World War I, to the growing interest of people in a new medium that made the screening program an entertainment choice in the colonial era. The rise in the screening business in Surabaya, ranging from canvas and bamboo tents to luxurious buildings that stimulated spectator mobility, gave us clues about the early evolution of the urban landscape of the city of Surabaya and its identity politics which had not always been successfully carried out by the Dutch colonial government.

Guest From Outside The Port

More than one century later since Talbott set foot in Surabaya, Tanjung Perak and film still act as a bridge connecting historical ties between Indonesia and the Netherlands. It is Yunjoo Kwak, an artist from South Korea who lives in Rotterdam, who tried to unravel the historical bond. She also tried to unravel the building of historical narratives across various disciplines– a process which certainly had the risk of becoming “eclectic” narratives, that revolve around the practice of mix-and-match only because of a lack of knowledge and an inability to articulate what needed to be further studied in her research.

Through “Only The Port are Loyal to Us”, Yunjoo provided an opportunity for us not to be easily tempted into retrospective patterns like those offered by historical films—or when many parties claim that historical films were limited to “films that presented something that had already been past”. That the evidence that could still be referred to today made us understand the extent of the boundary line between events, stories, archives, documents, and allegorical reflection in the film.

Instead of choosing a narrative form, Yunjoo presented an experimental documentary which she composed by collating footage about Tanjung Perak past and present. Yunjoo let the film joked through silence supported by animation and scoring for almost the entire duration. Yunjoo, it seems, wanted to share the visual experience in her understanding as an advanced stage–where the public watching not only enjoyed visual presentation, but also reviewed what was trying to be displayed visually. Such visual experiences were important today because it was like drawing us back to the debate about how “truth” works.

I refreshed our memory a little about the philosophical debate between the correspondence and coherence theories of truth. If the correspondence theory of truth was that the truth must be in accordance with the reality out there, then the coherence theory of truth saw that the truth was something that was intact in its own structure without having to match the reality out there. To enrich the debate I also included the concept of nonrepresentational understanding of truth or infinitive truth: that all forms of knowledge had the same degree of truth. My aim in presenting this philosophical debate is to make us understand the way of viewing the concept of truth which is still limited by a jumble of entities.

“Only The Ports are Loyal to Us” was a story bridge that connected collective memory of events from colonial times to the present day. About how the subject-object relationship that, despite the differences of time and distance, still had the opportunity to guess what had happened in the past and its influence in the present. As a bridge to the story, Yunjoo’s work was a link that leads us to look back to something that was never really clear: history. I used the word “bridge” as a metaphor such as how Yunjoo chose “port” and “film” in her role as a connector, or in this case, maybe, we could agree to use the word medium.

As a medium, Yunjoo should realize that it was impossible for her to cover all the details of events and “truths” such as how unilateral claims to history were impossible to be free from certain narratives. Conveying historical “truths”, as I know them and studying them, would never be able to match the details of historical events themselves–so that any attempt to unmask history that was claimed to be “truth”, that was exactly the same as historical events itself, was almost impossible. At this point, the medium only helped us to refer to events and guess the level of information conveyed as the pieces that complete to be read or reconstructed it, not to be believed as the only “truth” information of history.

When it came to this stage, the film medium, as chosen by Yunjoo, became relevant to be discussed as one of the speaking choices. It presented the possibilities to avoid being trapped as we read historical texts that were considered monumental and authoritative. That history could be conveyed in a flexible manner, involving everyday and trivial matters. Even at some point blurred between what was documentary and fiction–provided that this blurring of boundaries was interpreted as an effort not to rush to assume that what was conveyed through the medium was complete and absolute truth.

Yunjoo, and perhaps, those of us who witnessed Yunjoo’s work, were guests from outside the port who had the opportunity to observe clashes of historical and past texts. Through a metaphorical presupposition that could be called a port or a bridge that was dubbed into the medium of film, we were not in axiomatic experience, but rather a liminal one. The experience of being in the liminal space gave us the status of ambiguity: that was not located “here” or “there”. This state of being made us a guest, a stranger, who was entitled to get and process the story, but had no right to claim to be the one who knew the truth about the story.

This status also could later be used as a critique of the workings of history when determining objectivity and restoring it into various medium choices. As Julian Barnes once wrote in one of his novels that, “History is certainty that results when memory imperfections meet with a lack of documentation.” That sometimes history was considered certainty right when its own footing was incomplete. That Yunjoo herself must also be prepared to accept criticism and be able to articulate her ideas about history based on the linking of memories and colonial heritage monuments that bridge Indonesian-Dutch relations, right at a time when the medium could only display fragments of truth.

By choosing a film medium over other media choices, Yunjoo should also have moved away from what Talbott did when he first conducted a screening program in Surabaya. It was not enough to just document the hustle and bustle of the ships at the port and their journey from the Netherlands to Indonesia. It was not enough just to do a screening and exhibition program. She also had to be critical about the colonial practices and perspectives which to these days still plague European societies and transmit them to Asian communities, especially with regard to managing documents, archives and their convenience as an authoritative spokesperson of history.

*This text is the original version of “The Port Remains the Same” written by Yogi Ishabib, and is part of Yun Joo Kwak’s exhibition titled “Only The Ports are Loyal to Us” This work has also been published on the official website of the East Java Arts Council (DKJT).

Page 1 of 912345...»Last »