Luntas: The New Wave of A Ludruk Troupe

The art of Ludruk is always undergoing updated. This doesn’t mean that this art form is like an ornament that can’t be enhanced or changed. Change is something absolute in its essence because Ludruk is like an organism. It will evolve and grow according to the conditions of the times and its environment. This is demonstrated by one of the pioneering Ludruk groups, Luntas.

Luntas is a Ludruk group that emerged in the post-New Order (Orba) era, roughly born in 2016. The age of this Ludruk group can be marked through its 6th anniversary, titled “Anniversary Nemta6en,” held on January 23rd recently. To commemorate it, a celebration event was held at Mbah Cokro’s eatery in Surabaya, and the play staged was titled “Babad Alas Surabaya: Jaka Jumput.”

Through this performance, Luntas continues to show its consistency as a pioneering Ludruk group. For 6 years of creating, this group has brought so much freshness to the world of Ludruk art, especially in Surabaya. The refreshment in their anniversary performance is shown in the promotion of the performance and comedy on stage.

They actively promote and introduce through social media. They package it differently from old-style Ludruk groups. If, in the past, before the arrival of this group, Ludruk art was promoted using megaphones—by going around the village—or written on a bor board—the term used by Ludruk artists for a blackboard advertising the play to be staged—then Luntas presents it differently.

This Ludruk group uses audio-visual media in the form of promotional videos for the play they will perform. They frame it with action film-style videos and very contemporary style. This can be seen on the Facebook page of one of Luntas’ founders, Roberts Bayoned. The one-minute video presents information about the play to be performed at the event.

Moreover, this Ludruk group has also frequently documented every performance they have. Then, they upload the recordings to digital media, especially YouTube. These recordings can be accessed through the YouTube channel of SMC Mediavisitama or Ludruk Luntas Indonesia Channel. There is so much documentation of this group’s performances on both channels.

The promotion and documentation pattern of this Ludruk group’s performances have shown a change within this art form. Ludruk artists are not only starting to follow the current of the times, but they also still keep this art form enjoyable for a wide audience. Thus, Ludruk can broaden its audience reach to the virtual public.

Additionally, this renewal is not only manifested through these aspects, but this group also continuously renews its comedy style. Because, based on the acronym of this group, they carry the slogan, “Ludrukan Nom-noman Tjap Arek Suroboyo” (Luntas). This slogan also brings forth a comedy style that is very attached to this group.

This comedy style was also presented in this performance. Luntas presents a very contemporary comedy style and outside the usual conventions of Ludruk groups. In an interview, Robert explained that he was inspired by Japanese comedy style that uses a blackman to provide background effects in each of its shows. This figure wears black clothing, blending with the stage background, as if invisible as a character in the play.

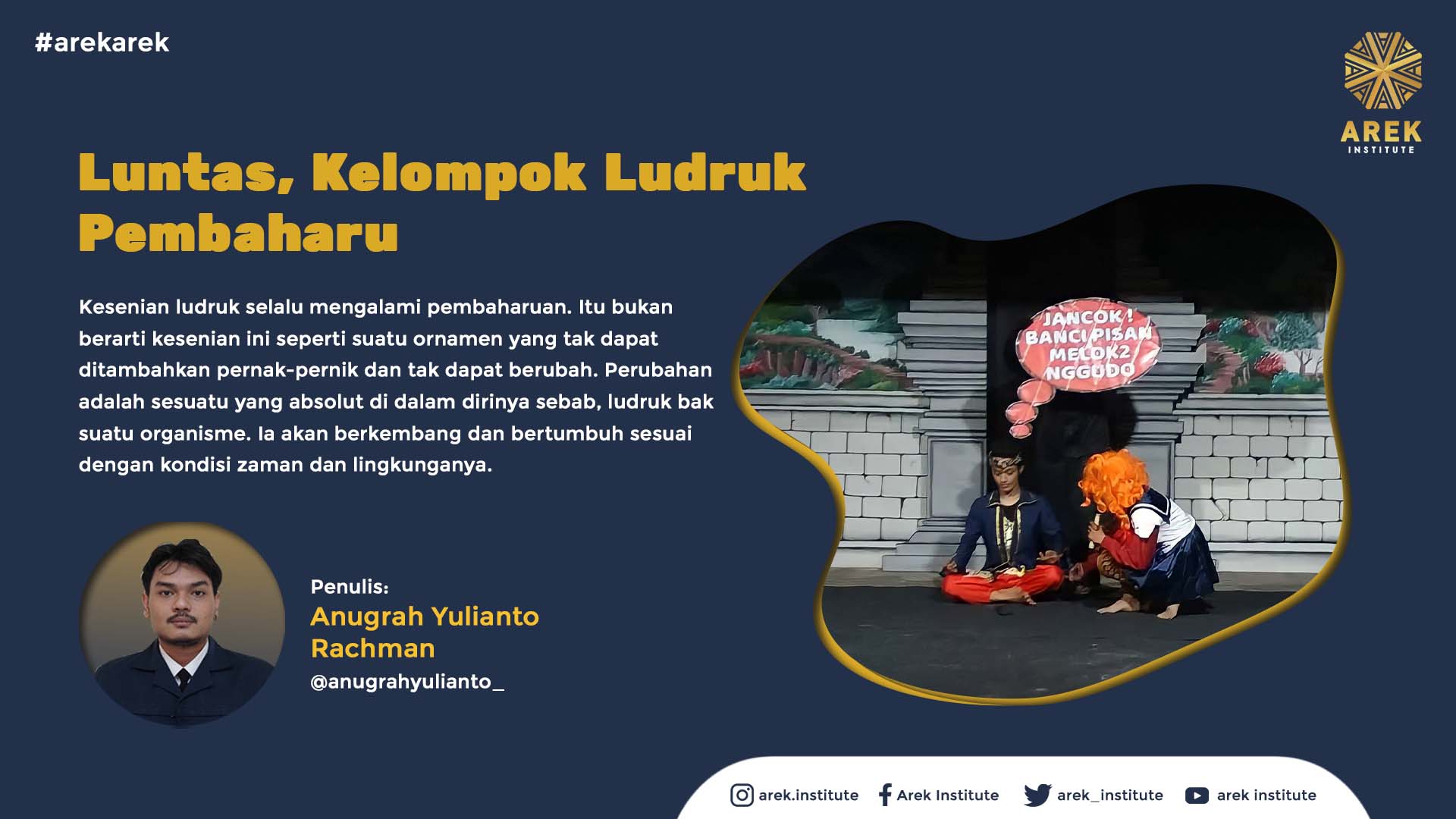

He gave effects to the robes worn by one of the characters in his performance. For example, in a scene where Jaka Jumput is tempted during his meditation, this blackman figure provides an effect with the writing saying “Waduh digudo setan”. The scenario occurs when Jaka Jumput is meditating, and a demon wearing a black robe is disturbing his meditation. Then the Blackman places this writing above Jaka Jumput’s head.

In addition to the Japanese-style comedy figure, such as the use of a Blackman, the ambiance of this play’s performance is filled with unusual costumes and surprises compared to most Ludruk plays. Again, in the midst of his meditation, a transgender woman comes and teases Jaka Jumput. Then, the blackman provides another writing effect like: “Jancok! Banci Pisan Melok2 Nggudo”. Interestingly, the transgender character in this play does not wear the typical cross-dressing costumes of old-style Ludruk groups. She wears a Japanese anime costume, Sailor Moon, wearing an orange wig—exactly like one of the characters in that anime.

Even during a battle scene of Prince Sumenep in the play, it is presented in a very unique and different way. This Ludruk group chose to provide the background sound effects of that battle with songs from that anime. The song adds a dimension of tension as well as humor to the battle scenario because not many Ludruk groups use a comedy concept like this group.

The renewal of both the play and the promotional pattern turns out to be a form that has indeed been made a character of this Ludruk group. This was stated by Robert during the opening of this event. He mentioned that Luntas has been striving for 6 years to create a generation of audience because Ludruk art, in the present time, needs to have an audience reach from the current generation.

Therefore, Luntas adopts the slogan that it is a young and modern Ludruk group styled like Surabaya. This is because, in their performances, they always incorporate the cultural language of the Arek community, which is characterized by Surabaya terminology. This is also marked by the comedy style of this Ludruk group, which is not the same as most Ludruk groups. Luntas presents a comedy dimension that is far different from other Ludruk groups.

In short, the Ludruk group Luntas is an oasis in the midst of the Ludruk art world. This group brings a breath of fresh air in all its Ludruk art activities. This renewal has proven capable of making this Ludruk group a group with its own unique characteristics and identity.